Today's collector is most likely to find twisted strands of opaque-white glass in the inexpensive paperweights that are made in Italy and sold in this country in gift shops. This filigree, or latticino, glass, which frequently incorporates colored threads and ribbons as well, is often trimmed with "gold" dust. It continues a centuries-old tradition. Although opaque-white glass -- made by adding tin oxide to the batch of molten glass-metal -- was known to the ancient Egyptians and Romans, the Venetian glassmakers of the sixteenth century perfected it.

During the first half of the eighteenth century, opaque-white glass began to be used in England, as it was used earlier in Venice, as an inexpensive alternative to porcelain. The English product has been mainly attributed to glasshouses in the city of Bristol, although it was probably also produced in other glassmaking centers, such as London, Newcastle, and the Stourbridge area. Opaque-white glass began to be used in the stems of wine glasses about 1755, and the style continued to be popular until about 1785.

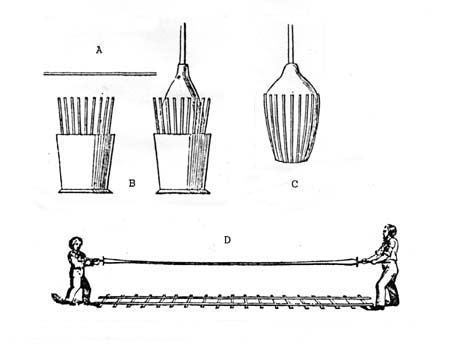

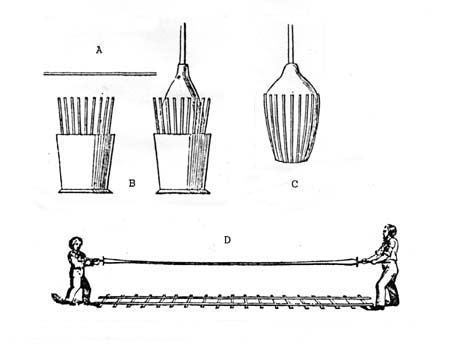

In the making of the twisted stems, cakes of opaque white glass were first made into rods. As shown in the following drawings, from Pellatt (1849), these rods (A) were then placed, fence-like, in a cylindrical mold (B), picked up by a gather of lead glass (C), coated with a layer of clear glass, and then stretched and twisted by a team of two workmen (D), somewhat in the manner of a taffy-pull. The solid length of glass, after cooling on a track or ladder, was then cut into lengths appropriate for the three-part glasses that were to be made. Such glasses have logically been informally called "cotton stems".

The operation illustrated here produced a multiple-spiral opaque twist (MSOT), a basic form, analogous to the multiple-spiral air twist (MSAT), that was often used alone or together with the simple rod itself. The use of molds, and repetition of the process, permitted a great variety of stems to be made. Instead of only the eighteen or so patterns that one can find in the stems of glasses with air twists, there are scores of opaque-white patterns. It has been said that no individual collector could possibly find a sample of each pattern that was made.

"After dinner [in August 1768] [we] saw the different operations in making a wine-glass and beer ditto and putting the white in the stem; the workman gave us a specimen of the white metal".... The actual making of opaque-white glass offered no great problems at this time, and for those who had not mastered the art the material was available in rod or cake-form from those who had.... The making of opaque-twist glasses was probably practised in all the main English centers. (Charleston 1986, pp. 148-149)We have seen, in the air-twist file, that the double-series air twist, where one formation winds around another, is more rarely encountered than a single-series air twist. With opaque-white twists the situation is reversed. Apparently double-series opaque-white twists (DSOT) proved to be more popular with eighteenth century customers than the simpler single-series twist and many more of them were manufactured. The glassmakers were not reticent in displaying their virtuosity; they probably competed against one another to produce ever more elaborate twists. Even triple-series twists were made, but they are rarely found today.

The flexibility provided by the molds also enabled the eighteenth century glassmaker to incorporate both solid and air elements in the same stem -- the mixed twist. On occasion he used colored rods, either opaque or translucent, to produce the rare color twist.

The examples in this file illustrate a few of the types of opaque-white twisted stems that the collector can expect to find today. At first glance, the single-series twist below, left, appears to be a pair of alternating spirals of simple, thick threads. But on close inspection each thread is seen to be a cable, composed of bundled rods. This wine glass is unusual in that the opaque-white spirals have a definite pinkish tint. In actuality a great range of color can be found in "the color of white" -- milk white, ivory white, etc. None are thought to be typical of any particular manufacturer.

The single-series twist shown below, center, is called a lace twist outlined and is widely regarded as one of the loveliest twists that was produced. The network of criss-crossing strands, similar to the vetro a reticello technique of the Venetians, do not actually touch each other. A cross-section through the pattern shows a pointed ellipse with heavier rods used at the end points.

The pattern illustrated below, right, is probably the most commonly found type of double-series opaque-white twist. The number of plies, or strands, in the spiral band can vary, and they can be either coarser or finer than what is shown here. The inside twist, here a gauze, is nothing more than a thin multiple-spiral opaque twist.

LEFT: Wine glass; ogee bowl; SSOT -- pair of spiral cables; c1760; H = 6.1" (15.5 cm); $150. CENTER: Wine glass; RF bowl; SSOT -- lace twist outlined; c1765; H = 6.5" (16.5 cm); $210. RIGHT: Wine glass; slightly waisted ogee bowl with molded basal flutes; DSOT -- 13-ply spiral band outside a gauze column; c1765; H = 6.1" (15.5 cm); $210.

An alternating pair of thin gauzes surround a gauze column of greater diameter in the glass below, left. Wheel-engravings on this glass and its neighbor, below center, are rudimentary, consisting of stems, leaves, and berries. The latter are generic, merely suggesting the use for which the glasses were made -- the serving of cordials made from various fruits. The small capacity of the bowls -- about one ounce -- is typical of glasses made for cordials, as are the disproportionately long stems. Glasses ten inches tall are known, but they are rare. The final glass from this period, below right, is a good example of a double-series opaque twist with two knops. Examples with as many as four knops are known, but they are rare. Even stems with only one or two knops are not common.

LEFT: Cordial glass; engraved RF bowl with solid base and molded basal flutes; DSOT -- alternating pair of spiral gauzes outside a gauze column; c1765; H = 6.25" (15.9 cm); $160. CENTER: Cordial glass; engraved RF bowl with solid base; DSOT -- four spiral threads outside a gauze column; c1765; H = 6.5" (16.5 cm); $200. RIGHT: Wine glass; bell bowl; DSOT with shoulder and central knops -- four spiral threads outside a gauze column; c1770; H = 6.4" (16.2 cm); $100.

Attention is drawn to a feature common to two of the above glasses -- first row, right and second row, left. These glasses have shallow flutes around the bases of their bowls. They were possibly produced by blowing the gathers into open, one-piece molds -- the so-called dip molds -- that were grooved on the inside. It is believed that such flutes, which are often found on decanters of the period, were used in order to obscure somewhat any sediment that would have settled out of the liquid. The flutes illustrated here could also have been made by tooling.

Drinking glasses with bowls decorated with enameling instead of wheel-engraving were also popular, and this technique nicely compliments the white strands in the stems. The work by William and Mary Beilby of Newcastle during the 1760s and 1770s is particularly noteworthy (Rush 1973). Landscapes, sporting scenes, simple vine-and-grape patterns, and elaborate armorials are some of the subjects depicted on these glasses. The collector is unlikely to find any genuine Beilby glass casually offered for sale, although inferior enameled examples, sometimes proporting to be by the Beilbys, appear from time-to-time.

In the goblet shown below there are several wheel-engraved symbols indicative of eighteenth century Jacobite activity. But is the glass genuine? Or is it a forgery or fake? Its shape is that of the so-called "firing glass" of the period. Such a glass, with its thick foot, was made to be thumped on the table in response to toasts, here presumably made to the Stuart regent, Bonnie Prince Charlie, who was in exile on the Continent following his defeat at the Battle of Culloden (1745). But this glass is about twice the size of a true firing glass. Moreoever, the diameter of its foot is one-half inch less than the diameter of its rim. Its lead metal has a very slight yellowish cast, and there are no tool marks on its bowl. An eighteenth century origin for this glass is, therefore, doubtful.

Older reproduction of a Jacobite drinking glass. Trumpet bowl wheel-engraved with Jacobite symbols (open rose, rose bud, oak leaf, radiant star, and the word FIAT). DSOT -- four spiral tapes outside a loose gauze column; H = 7.9" (20.1 cm); $210.

Doubt becomes certainty thanks to the research of G. B. Seddon who has photographed hundreds of Jacobite glasses and has thoroughly analyzed the style of their engravings (note 1). The engraving on this glass corresponds exactly to examples that can be found in two museums in England and Scotland. But those glasses can unequivocally be shown to be of early twentieth-century manufacture. It follows that this must also be true of this "Jacobite" glass. The engraver, who copied from eighteenth century examples with considerable fidelity, is thus far unknown. Also unidentified is the glasshouse; several British factories reproduced Georgian glassware during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The goblet can be thought of as an example of late Victorian or Edwardian nostalgia. As such it is as honorable as it is handsome and should be labeled a reproduction, not a forgery or fake. There is no record of it being offered for sale as anything other than what it is -- a well-made drinking glass of unknown age and origin (note 2).

The "Jacobite" glass underscores the great care that must be taken when buying old glassware, especially items that could have considerable value. Intentional deception is probably not as frequently encountered today as in the past, because buyers have become better informed. But unintentional deception, based on ignorance, is still all too common. Collectors and dealers alike would do well to take the time to do research. It is required if one wants to buy and sell antique glassware with confidence.

NOTES:

1. The writer appreciates comments received from Dr. Seddon concerning the "Jacobite" goblet. (See also Sedden, G. B., 1979: The Jacobite engravers, The Glass Circle, No. 3, pp. 40-78.

2. During 1988 the writer came across a reference to a so-called Jacobite drinking club said to have existed in NYC during the early years of the twentieth century. Unfortunately he failed to note where this reference -- which was, in any case, quite vague -- appeared. He would appreciate hearing from any reader who can supply this information. The reference was contained in a book about general antiques that was probably published in the 1970s. Jacobite drinking clubs, probably somewhat whimsical, are said to have existed at Oxbridge colleges in England as late as the First World War. It is possible that the "Jacobite" glass shown here was made for such a purpose, if not for an American one.

Updated 23 Jul 2002