English drinking glasses of the eighteenth century with wheel-cut stems -- like their cousins the "twisted stems" -- are occasionally seen today at antiques shows, shops, and auctions. The decorating technique for wheel-cut glasses is, of course, radically different than what is employed in the making of air-twist and opaque-white twist stems. Whereas the latter two categories were made when the glass was hot and pliable, cutting is a cold-glass processes.

The tradition of cutting stems is still with us, usually in the form of simple vertical flutes or panels. There are often six of these, although the number can vary. This pattern can also be found among surviving specimens from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. However, stems cut in patterns of diamonds and hexagons have greater interest to collectors. These same designs are also found on the necks of bottles and decanters, including those made during the American brilliant period.

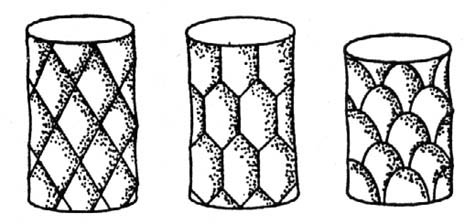

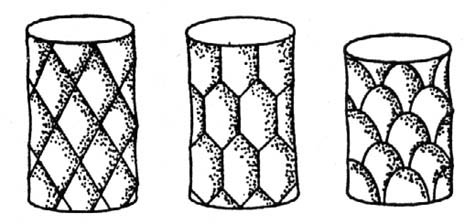

All cutting wheels are based on three profiles: flat, convex, and V-shaped. Usually a wheel with a convex profile was chosen to produce the hollow diamonds and hexagons found on antique faceted stems. The hollow figures are produced by cutting arrays of bullseyes (punties) that overlap previously cut arrays. By varying the spacing between the bullseyes of each array different patterns are produced, as illustrated by the following drawings (from Gros-Galliner 1970):

LEFT: Hollow diamonds. CENTER: Hollow hexagons ("honeycomb"). RIGHT: Scale cutting.

The wine glass shown below, on the left, has a typical faceted stem of hollow diamonds. Sometimes the cutting was extended to cover the foot, and sometimes it would creep up the bowl as well. But here the foot is uncut and the cutting on the base of the bowl is limited to slice-cut "sprigs" that fill empty spaces between the top-most row of hollow diamonds.

Although drinking glasses with faceted stems were probably made in England before 1720, their heyday did not occur until much later, when they replaced the opaque-white twists almost entirely (Elville 1967). Although the reason for this change is not entirely clear, the Glass Excise Act is usually given as a contributing cause. This tax was passed by Parliament in 1745 to raise money for England's several wars. In 1777 the tax was doubled and now included the opaque-white metal that was used to make opaque twists.

Cut glass was for the wealthy, and cutting was more exploited on dessert-glasses and tablewares than on drinking-glasses, which offered less space for its deployment. The stem and base of the bowl are the main fields for decoration, which really permit only vertical fluting or diamond-faceting. Rarely is a bowl cut all over and foot panelled and scalloped. (Charleston 1986, p. 178)

The wine glass on the right, below, has a stem cut in elongated hollow hexagons. The arrays of bullseyes were cut with the stems held parallel to the floor, that is, perpendicular to the cutting wheel, not parallel to it.

LEFT: Wine glass; ogee bowl; stem cut in hollow diamonds; c1775; H = 5.75" (14.6 cm), $110. RIGHT: Wine glass; round funnel (RF) bowl; stem cut in hollow hexagons; c1785; H = 6.25" (15.9 cm); $150.

No public sale of an extensive collection of eighteenth century drinking glasses has been held during the past thirty-plus years, and therefore it is difficult to price the different categories of stem-styles. This is one reason why the actual price paid for each glass is given in these files. By comparing these prices with the scattered auction and show reports that are available, it is possible to arrive at a few generalizations.

Of the three stem-styles, the faceted stems are the least expensive. Good examples can be found in the $100 to $200 range, with the higher priced items carrying simple engravings. Elaborate engravings, and those with social and political interest, increase prices considerably. For example, the estimated price of the pastoral glass shown above is between $750 and $1000.

Glasses with opaque-white twists in their stems are slightly more expensive than the faceted stems, with good examples often found selling between $150 and $250. Glasses with air twists, the oldest of the three groups, are the most expensive, usually priced in the $200 to $300 range. Again, in both groups, engravings of quality will raise prices significantly. The cable (air) twist engraved glass shown in the Air-twist file sold for $500 in 1988.

The condition of any glass intended for purchase must, of course, be considered. Thirty years ago any chip would make a glass virtually unsalable unless the glass were a rarity. Today experienced collectors are somewhat more realistic when judging the condition of glass of this age. But at the same time there is, naturally, a strong preference for glassware in so-called mint condition. This has led to the repairing of damaged glass, euphemistically called "restoration".

The arguments for and against the repair of any glassware, not just eighteenth century drinking glasses, are much too complex to be discussed here. The subject is considered in a separate file. At this point the reader is simply cautioned that many repaired antique glasses exist and more and more of them will undoubtedly appear in the future. It is recommended that the collector adopt a conservative approach toward the repair of any glass in his or her charge. For example, never have the rims of antique glasses ground in order to remove nicks and minor chips. In buying old glassware make sure that the glass of interest has not been "worked on" or, if it has, that you are aware of this fact and that it is reflected in the price asked. A repaired glass should always be priced less, sometimes considerably less, than an untouched glass, even one with minor damage.

It is truly remarkable that so many drinking glasses from the eighteenth century exist for today's collector, and, moreover, that they can be found at reasonable prices. They are recommended, however, not as investments, but as objects of beauty that can provide fascinating glimpses into times long past. Only the rarest examples need to be locked away and used for display only. Most should be enjoyed in today's social settings. Given reasonable care they can be expected to provide pleasure to the collector and his descendants for a long time to come.

Updated 21 Jul 2002