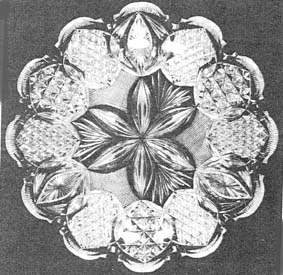

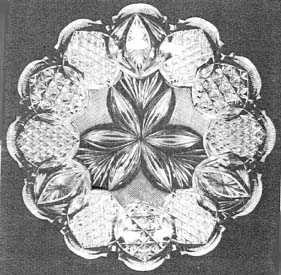

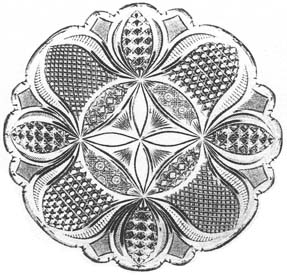

It is generally believed that the two cut-glass dishes in this file were displayed by the Boston & Sandwich Glass Company at the Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876. There is further agreement that they were designed and cut by Nehemiah Packwood, foreman of the Sandwich cutting shop at this time. The writer believes, however, that it is possible that only one dish was actually displayed at the Convention because the other one contains what is thought to be an error. The two dishes are analyzed below in order to provide evidence for this hypothesis which is based on the principle of symmetry.

The dish with the problem is called no. 1 in this file. While it could have been displayed as-is ("maybe no one will notice"), it might have been replaced with dish no. 2, or, as a third possibility, both dishes could have made it to Philadelphia.

The provenances of the dishes should give us clues, if not hard evidence. Luckily, the second dish (called a "bowl" or a "shallow bowl"), with dimensions D = 11.75" (29.8 cm) and H = 2.88" (7.3 cm), has a provenance that appears quite strong (Wilson 1994, p. 636). In addition to being illustrated in Wilson's book, the dish is also shown, but only briefly discussed, in an article by Thomas A. Crawford, Jr., "The attribution of cut glass prior to the brilliant fashion" (The Acorn, No. 2, pp. 41-71 [1991]). This dish is currently at the Sandwich Glass Museum (acc. no. U.7.54).

Unfortunately, a provenance for the first dish, which was shown at an exhibition of cut glass at the Corning Museum of Glass in 1977, is lacking. The catalog that accompanied the exhibition provides little information, only that the dish (called a "plate") was cut by Packwood, has a diameter of 10.1" (25.7 cm), and was owned at that time by two individuals in New Jersey (Spillman and Farrar 1977, pp. 34-5, 89). It too is now in the collection of the Sandwich Glass Museum. The writer is seeking additional information for both dishes.

Great care was taken by Packwood in the design of dish no. 1. The border design and the central design are both symmetrical. But, as can be seen in the illustration below, on the left, the pattern as a whole is asymmetrical. It is "off-kilter". The writer contends that this oddity was not intentional but is the result of an error that occurred when the dish was cut. The image on the right shows what would have resulted if the central design had been shifted 30 degrees counter-clockwise (the border design remains in a fixed position). The result is symmetrical; is far more satisfactory; and is likely to have been the intention of the designer. Symmetry would also have resulted if the central design were shifted 30 degrees clockwise. The only requirement is that the central design's split-vesica motif be cut opposite the border design's cross-cut diamond motif. As indicated in the analysis that follows, both motifs were cut six times. The correct orientation might not have been as simple as it sounds today when one realizes that it was probably cut under shop conditions, which could have been distracting, even to an experienced cutter. At any rate, the error did not preclude the completion of the dish. But was it actually displayed at the Centennial Convention?

Border Design (12 overlapping near-circles):Center Design:

- (6) cross-cut diamonds at 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 o'clock

- (3) quarter diamonds at 2, 6, and 10 o'clock

- (3) single star within vesica, bordered with fans (2 or 3 ribs), at 4, 8, and 12 o'clock

Also, a total of 12 small split vesicas (one for each pair of overlapping near-circles)

- (6) split vesicas at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 o'clock

- (3) strawberry (fine) diamonds or cross-hatch at 3, 7, and 11 o'clock

- (3) fan (7 ribs) at 1, 5, and 9 o'clock

In the above tabulation, the frequency of occurrence for the motifs in both the border and central designs is 6 + 3 + 3, a total of 12 for each design. Twelve is the number of near-circles and is a mutiple of 6, and/or 3, and/or 2. The designer chose three motifs for each design and used them 6 and 3 times, the latter twice, in order to arrive at the required total of 12. The expression "near-circles" was first used by the late glass scholar Estelle Sinclaire in an article in which dish no. 1 is briefly discussed (note 1). The near-circle figure is actually a vesica, formed by a pair of miter cuts. However, because this term is used elsewhere in this analysis, the writer uses near- circles to avoid confusion.

In the following tabulation, for the second dish, the frequency of occurrence is now controlled by the number 8: 4 + 2 + 2 for the border design, and the same for the center design. Symmetry is centered along the 45 deg/225 deg and 135 deg/315 deg axes. (North is 0 deg.)

Border Design:Center Design:

- (4) vesica contains quarter diamonds and is bordered with serration, at 0, 90, 180, and 270 deg

- (2) ogee arch contains hobnail and is bordered with zipper cuts, at 45 and 225 deg

- (2) ogee arch contains cross-cut diamonds and is bordered with zipper cuts, at 135 and 315 deg

Also, a total of 8 kite figures that contain strawberry (fine) diamonds, or cross-hatch, between each pair of the above motifs

- center: (4) four vesicas (pillar cut) form a quadrafoil flashed with fans (9 ribs)

- inter-medium: (2) vesica contains triple-mitered cane, at 45 and 225 deg

- inter-medium: (2) vesica contains single-mitered cane, at 135 and 315 deg

Dish no. 2, with its striking symmetry, seems to confirm the writer's argument that the asymmetrical dish no. 1 is an aberration. Note, also, how Packwood has taken balance into account in dish no. 2: The largest areas, the ogee arches, use relatively simple motifs -- hobnail and cross-cut diamonds -- while the smaller areas, the inter-medium vesicas, use more complicated motifs -- single-mitered and triple-mitered cane. In addition, note how the similarity of the chosen motifs is a positive factor in enhancing balance: hobnail and cross-cut diamonds are paired, as are single- and triple-mitered cane.

Dish no. 1 displays six motifs: single stars, cross-cut diamonds, quarter diamonds, fans (2, 3, and 7 ribs), strawberry (fine) diamonds or cross-hatch, and split vesicas (large and small). Dish no. 2 displays ten motifs: quarter diamonds, hobnail, zippers, serration, cross-cut diamonds, strawberry (fine) diamonds or cross-hatch, single-mitered cane, triple-mitered cane, fans (9 ribs), and pillar cutting. Note the absence of motifs which are usually assumed to have been in use in 1876: star and hobnail, Brunswick star, hobstar (8-pt), double-mitered cane, step cutting, bullseyes, hollow diamonds and hexagons, and flutes.

Both dishes have the same, elegant rim treatment that includes scallops, fine serration, and U-notches. This rim style undoubtedly indicates that the dishes were considered special items by the B & S company. An identical rim is found on one of Dorflinger's most famous (special) pieces, the W. C. Fowler compote, dated 1860, which is shown and described in The Glass Club Bulletin, winter 1981-82, pp. 1, 3-4 and is now at the Corning Museum of Glass (acc. no. 2003.4.109). Another example of this rim style, sans serration in this case, is its use on most realizations of Hawkes' Panel pattern of 1909 (pat. no. 40,195).

It is hoped that this file will stimulate interest in American glass as it was cut at the time of the country's Centennial, a time of transition between the so-called "middle" and "brilliant" periods of cut glass. As this file shows, the cutter had a diversified repertory of motifs at his disposal. The flutes, diamonds, and bullseyes of the middle period continued to be popular, but they were supplemented with more complicated motifs that would eventually help to usher in what is today called the brilliant period.

NOTE:

1. "Brilliant-Cut Glass: A Reinterpretation" by Estelle Sinclaire Farrar appeared in the Jan/Feb 1981 issue of Art & Antiques, pp. 86-91. Farrar was of the opinion that "popular taste" at this time ignored the dish's style which, additionally, "had little or no effect on the cut-glass industry". To the writer these negative statements indicate that Farrar regarded the dish as a commercial product, which it is not. As emphasized in this file, the dish is a demonstration dish. It merely brought together, in one place, a number of motifs that were routinely used by designers of cut glass. The pattern was of little importance as long as it made it possible to display as many motifs as possible. In fact, a table service cut in patterns such as those on these two dishes would have been aesthetically overpowering and impossible to cut completely. In addition, no company would have been expected to produce demonstration dishes for sale; the demand would have been much too limited. As a result of these factors, demonstration dishes of this period would have had little or no influence on either public taste or the cut-glass industry itself.

Updated 19 Aug 2005