Related file: The Briggs patents are listed in the hawkes2.htm file in Part 2.

It is little wonder that T. G. Hawkes asked his accountant, Spencer & Mills of Corning, NY, to handle the business of obtaining patents to protect two patterns, both called Louis XIV, that the Boston dealer Richard Briggs proposed to market. Briggs delt in fine glass and china and was a good customer of Hawkes's. In return for his paying the cost of the patents, Hawkes was granted exclusive rights to produce the patterns for Briggs. The fact that Spencer & Mills attended to the details of patenting, and not Hawkes directly (at least not for most of the time), is not surprising given the situation in Corning early in 1889. At this time Hawkes was heavily involved in preparing his glassware for shipment to Paris in early March for installation at the Universal Exposition that was scheduled to open in May. Daily activity at Hawkes's factory must have been hectic!

Spillman (1996) has reviewed the correspondence between Hawkes and his patent attorney, Knight Brothers of Washington, DC, at this time. She presents a complete summary of the correspondence between these two concerns. However, she has ignored much of the correspondence that took place between Spencer & Mills and Knight Brothers; correspondence that provides additional insight into the Briggs patents as well as giving us practical information concerning the patenting process as practiced during the late nineteenth century. This corresondence is reviewed in this file which also includes the introduction of a "new" Louis XIV pattern, one that did not come to light until 2006. It matches the cut glass section of the earlier patterns but has a slightly different engraving.

We pick up the story on 28 Jan 1889 (letter to Spencer & Mills from Knight Brothers). All seems to be in order. The patent attorney has received the fees for the two designs that originated with Briggs and which were sent from Corning by Spencer & Mills. To complete the patents' applications, however, the patent attorney makes this request:

We shall need 12 photographs of each of the designs for which protection is sought, or, we can make line drawings. . . . The Examiner may now require line drawings as he objected to the photographs accompanying the other applications.

This is an early mention of the problem of image clarity that plays a major role later in the proceedings. The objection mentioned refers to previous applications from Hawkes, all of which included photographs, not line drawings. These photographs were of quite poor quality, as can be seen in Revi (1965, pp. 179-81).

During February and March 1889 the plot, summarized here, thickened considerably. Application papers for a third Louis XIV pattern, one that had a plain band (no engraving at all) were filed by the patent attorney who had received an application for it from Spencer & Mills, an application that was erroneously initiated by Briggs. Wrong move by all concerned! Hawkes quickly makes it clear that he intends to pay for two, not three, patents in the following letter that he sends directly to Knight Brothers (13 Mar 1889):

The two patents for Richard Briggs, for the designs for ornamentation of glassware, are for two designs -- one design with the fleur de lys border and a medallion, and the other with a fleur de lys border all around without medallion. You have photos for both of these. There are only two patents wanted.On the 15th Knight Brothers replied as follows:

We fully understood that it was the intention to proceed with two of the applications, but it was unfortunate that the application papers of the abandoned design were executed and returned to us instead of the correct papers. This has led to a misunderstanding as to which application was abandoned.

The word "abandoned" means that the patenting process had already begun for the third Louis XIV pattern, the one with a plain band. The next day Hawkes clarifies his postion in a letter to Knight Brothers, having, in the meantime, received a letter from his patent attorney that included sketches of all three Louis XIV patterns:

I did not care for three, but select two out of the three, which were duly sent to you.We have since sent you photographs that we supposed covered the two applications which were so sent to you; it seems there is some confusion about the matter, and we suggest that you return the applications with all the photographs so that we can determine which two of the three applications we wish patent[s] for.

The confusion was subsequently resolved and only two patent applications went forward: the first with a band of fleurs-de-lis and the second with a band of fleurs-de-lis and a wreath (or medallion). As indicated in the following quote from the second patent's specification the term medallion refers to the space enclosed by the wreath; it may be used for a monogram but also can be left empty: "a flower figure in the form of a wreath or circle surrounding a medallion presenting sprays and flowers extending in opposite directions". Note that in this second patent there is no mention of the fleur-de-lis motif; it is assumed to be present. The third Louis XIV pattern, the "abandoned" one with no engraving, is never mentioned again.

But the Briggs matter was not quite out-of-the-woods. Hawkes received more bad news about the patents from Knight Brothers in a letter dated 3 April:

The drawings in the form of mounted photographs [of the two designs] are rejected for indistinctness caused by reflected light. The Examiner requires either line drawings or clear photographs. We recommend line drawings because it is so very difficult to produce distinct figures from such brilliant surfaces, especially as the Examiner also requires sectional as well as plan views. It is very important that such designs be clearly shown. We find that it is becoming the custom to present line drawings (emphasis added). . . . To enable us to prepare [the line drawings] properly we should have two dishes, showing the different designs, loaned to us.Knight Brothers is clearly requesting actual samples of each design. On the 8th they write that the dishes "reached us this morning and were immedatedly placed in the hands of the draftsman." (letter to Spencer & Mills).

The matter was finally settled on 29 Apr 1889 when the two patents for Richard Briggs's designs -- the patterns as we know them -- were officially approved.

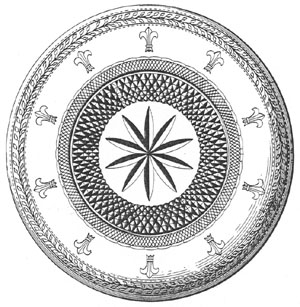

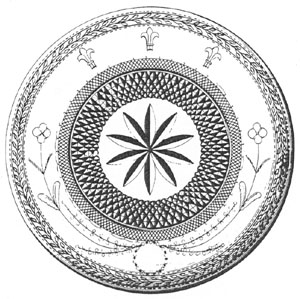

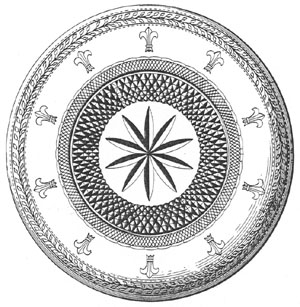

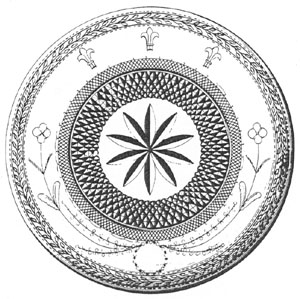

The first of the two patents, below on the left, is pat. no. 19,105. Its engraved design uses only the fleur-de-lis motif. Hence, it is suggested that its name be Louis XIV "Fleurs-de-lis". The second patent, no. 19,106, below on the right, has fleurs-de-ls together with a medallion (the blank space) that is surrounded by a wreath. The wreath is accompanied by a pair of floral sprays. Thus, its suggested name is Louis XIV "Fleurs-de-lis and Wreath".

Briggs's patents, accessible at the USPTO Web site include the "sectionals" mentioned above, in addition to the following plan views:

It was a surprise among most dealers and collectors when a heretofore unknown fourth Louis XIV pattern was advertised on eBay in 2006, then again in 2007. Some of the images from these announcements are reproduced here.

The tableware originally included the following shapes in a set that comprised 115 individual pieces, distributed among the following: champagne flutes, saucer champagnes, champagne tumblers, clarets, wines, sherries, water tumblers, and finger bowls with underplates. It is suggested that this new pattern be called Louis XIV "Fleurs-de-lis and Nosegays" (All images: Internet).

A wine glass from the set together with a close-up of the nosegay engraving:

The story of this unusual discovery is best told by its seller, Wendy Engelman of Aurora, IL in the following account (slightly edited):

This is a pattern that was patented by Richard Briggs and cut and engraved by T. G. Hawkes. Briggs supplied these to Marshall Field in Chicago. The engraved area varies somewhat from the patented versions. They were custom made for Peter J. Schaefer of Chicago. His parents were among the first to settle in Chicago. He became a very well known and loved businessman in the late 1800s through the 1930s. Schaefer was a multi-millionaire motion picture magnate. He was the first to bring movies to Chicago in 1905 and was the president of the Motion Picture Exhibitors League of America for many years. He fought censorship in the early years, exhibited his figure 8 amusement ride at the world's fair, and traveled the world with the high society of the time. He was active socially, as well as in business and in the community, His and his wife's homes were often featured in newspapers. His business was entertainment, and they certainly did a lot of entertaining themselves which probably explains why the set that I have has three different types of Hawkes marks, as he must have added replacements to the collection at different times, probably between 1890 and 1910 [slightly later dates are more likely]. There are acid-etched HAWKES, EDENHALL, and trefoil marks. The trefoil is on the water tumblers only.The EDENHALL and HAWKES trademarks in block print are illustrated as follows:These items were handed down to my mother-in-law 25 years ago. She inherited them from her cousin who was married to one of Peter J. Schaefer's nephews. The Schaefers had no children so everything was given to their three nephews upon Mr. Schaefer's death in 1940.

About 23 of the 115 pieces have little chips, either on the glasses' feet or on their top edges. Comparing the EDENHALL and HAWKES marked glass, there is a slight difference in the proportion of the engraved design. The clarity and quality is stunning on all.

The following is an example of the Louis XIV Fleurs-de-lis and Nosegays pattern on a finger bowl:

The new pattern will probably always be found signed, either with the trefoil or with the block letters HAWKES or EDENHALL. Note the use of the name Edenhall as a trademark, with no mention of Hawkes. An odd development when one considers the care T. G. Hawkes had taken previously to promote the Hawkes name and develop "brand loyalty", but Hawkes senior had died in 1913, and the company was now headed by his son, Samuel.

Spillman suggests that the Edenhall mark -- together with a line of glassware carrying a Signet trademark -- were used on "cheaper lines of glassware" (Spillman 1996, pp. 189-90). It is difficult to accept this assumption for the Edenhall line. Louis XIV tableware is clearly a luxury line. The Edenhall name was taken from the name given to a highly regarded goblet engraved by William Morse for Hawkes in the mid-1910s (Spillman 1996, pp. 174-5, 191). It would have made little sense for Hawkes to use the Edenhall name on glassware that was not in the luxury class.

Note that while Richard Briggs was particular about the shapes that were used in connection with his design patents, he never patented them. (Incidentally, the Louis XIV shapes are shown as shape no. 8608 in the 1896 J. Hoare & Company catalog, p. 11. It has been reprinted by the ACGA.) Briggs preferred that Hawkes use Baccarat blanks but the latter probably made use of whatever source was available.

Summary of the four Louis XIV patterns:

Updated 10 Sep 2007