An Informal Guide to Selected Items as Exhibited at the Corning Museum of Glass, July 2006

Highlights include: Discussion of the Star & Hobnail, Russian, and Persian patterns; examination of a questionable Chrysanthemum pattern; demonstration of a "figured" blank; appreciation of a "new" collectible -- Hawkes stemware from the 1920s to 1962; and examination of colored glass, layer-by-layer.

The purpose of a walkabout is to discover something new. Whether you are using this self-guide at the Museum or are elsewhere and must visualize the items discussed, you will discover new facts about American cut and engraved glassware. Please follow the guide's itinerary and do not let yourself be diverted. Make notes of those areas to which you would like to return after the tour; you will surely want to include the special exhibits: "The Glass of the Maharajahs" and "Splitting the Rainbow". If you move right along, it should take you less than an hour to complete the walkabout.

The are several reasons why certain items have been chosen for close examination: An item's label might contain incorrect information (note 1); or the item might illustrate a point that is often misunderstood; or the item might simply raise a question that begs an answer. In any case, background material is required. Spillman's THE AMERICAN CUT GLASS INDUSTRY -- where one can find several of the exhibited items -- together with similar publications fill this need. They are listed in a short bibliography ("Works Cited") at the end of this file. On occasion you will also be directed to relevant files in the writer's CD-R, A GUIDE TO AMERICAN CUT AND ENGRAVED GLASSWARE -- with which you are already familiar -- and to the Littleshop file which is online at www.geocities.com/jmhavens.geo/littleshop.html

Feedback is welcomed and will be acknowledged. A revised version of this file is planned for later this year.

The Museum's labels for the exhibited items are quoted verbatim and set in bold print. Accession numbers are given in the following format: year acquired.country of origin (4=USA).sequential number during year acquired. L = a loan item followed by this format: sequential number during year of loan.country of origin.initial year of loan.

Itinerary: The Brilliant Period

Follow the yellow "Tour begins" signs, pass through the Sculpture Gallery, and enter "The Glass Collection Galleries". Follow the curved wall on your right, past the "Glass of the Maharajahs" and "Jerome and Lucille Strauss Study Gallery" entrances to the large one marked "Corning: From Farm Town to Crystal City" where the walkabout begins.

Facing the Crystal City gallery, enter on the left and move straight ahead to the large case that contains the Hungerford glass window blinds. Note especially the Brooklyn Flint Glass Works decanter in front of the blinds. It shows that high-quality glass metal and cutting were attainable well before the beginning of the brilliant period of American cut glass. To the right you will find the following items that illustrate the differences between the Russian, Persian, and Star & Hobnail patterns, patterns that are often confusing, even to museum curators:

Cut Panel from a Door at St. Joseph's Church, Albion, New York. J. Hoare & Company, 1913. Coll, St. Joseph's Church. L.2.4.2006, lent by St. Joseph's Church, Albion, New York. (note 2). In order to discover that the motif that surrounds the large cross is a variation of the Russian pattern, tip your head 45 degrees to the right, and the familiar outline of the basic Russian pattern will be seen. Here is a fine point: With your head still tilted, locate any four pyramidal stars that surround one of the motif's decorated hobnails. At first glance it appears that these pyramidal stars are at the corners of a square, which is to be expected. However, because of the confining overall dimensions of the panel, this basic square grid has had to be altered slightly, so that the squares are now parallelograms. This is, of course, a minor point. Of more importance is the cutting on the motif's hobnails. If hobstars were used, the pattern would be identified as "the Persian variation of the Russian pattern", or more simply Russian-Persian. But because the hobnails are very large the cutter has chosen to cut 16-pt Brunswick stars on them. There is no special name for this particular Russian variation, although perhaps it too could be called Russian-Persian. Before leaving the door panel, note that the motif's pyramidal stars are "boxed in" with octagons; this an essential characteristic of both the Russian and Star & Hobnail patterns, and it differentiates them from the Persian pattern. This Russian variation, cut on such a large scale, is probably unique.

Move along to the first series of multi-shelves. Admire the Russian place setting, Item 3 on the Base, and the stemware to the right which includes the Persian and Star & Hobnail patterns. Notice the Persian goblet, Item 5 (90.4.13). One can easily see that its pyramidal stars are boxed in by a square, not an octagon -- an essential requirement for the pattern to be Persian. The cutting on the pattern's hobnails is usually a hobstar, as it is here, but it can also be something else, as we shall see. Note also that the goblet's rim has been ground to eliminate a chip, with the result that the rim's "bead" has been destroyed and the rim ground flat, thereby significantly reducing the goblet's value. The wine, Item 6 (85.4.24), is correctly identified here as Star & Hobnail, but incorrectly identified as Russian in Spillman 1996a (p. 47). The colored cut-to-clear wines, Item 7 (98.4.278, etc.), are also cut in Persian, but one must mentally connect the tops and bottoms of the cuttings in order to see that the pyramidal stars are boxed-in with squares (note 3). If you have truly excellent eyesight, you can see that hobnails in the Persian pattern are 12-sided rather than octagonal (at least theoretically!). Additional examples from this set are on display in the Rainbow Exhibit. Later we shall also find a good example of the Russian-Persian variation. (The Russian and Persian files in Part 1 of the GUIDE provide considerably more material on these subjects.) Next, consider Item 3 on Shelf 7:

Bowl Cut in "Starlight" Pattern, 1911-1915 (marked). 2003.4.84. This unusual shape, with an attached underplate, was probably meant for mayonnaise which was always served in a bowl with an underplate. The "Starlight" pattern was introduced in 1911. All true, but when this item was originally shown, in the so-called Texas Cookbook, an unusual collection of recipes and cut glass (Lone Star Chapter 1994, p. 301), and, two years later in Spillman 1996a (p. 155) it was photographed up-side-down. In both publications the item is described as a "toupee stand". However, it is highly unlikely that any such item was ever produced by any cut-glass manufacturer. If you are offered one, just turn it right-side-up like the Museum eventually did!

Refresh your memory of Hawkes' Chrysanthemum pattern with a look at Item 2 (99.4.78) on Shelf 6 before turning around and moving to the case at the entrance to the gallery.

Case with Hawkes' Brazilian candelabrum, Item 1: Bowl Cut in a Variation of "Chrysanthemum" Pattern. T. G. Hawkes & Company (signed), 1890-1895. 2005.4.25. This is a variant of Hawkes' "Chrysanthemum" pattern which was patented on Nov. 4, 1890. This version is slightly simpler with cut and polished plain sections. Whether this variation was ever marketed is impossible to know. Note that although the bowl is ideally placed under a strong light, and the acid-etched trademarks of Hawkes and Hoare are visible on the bottoms of bowls nearby, no acid-etched signature can be seen on this bowl. Note also that the first use of the Hawkes acid-etched trademark is believed to have occurred in 1901 or 1902, several years after the 1890-1895 period that has been assigned to this bowl. Nevertheless, the signature might be present. If it is, then it should be checked for authenticity. The acquisition date is late, 2005, and the quality of fake signatures has increased considerably during recent years.

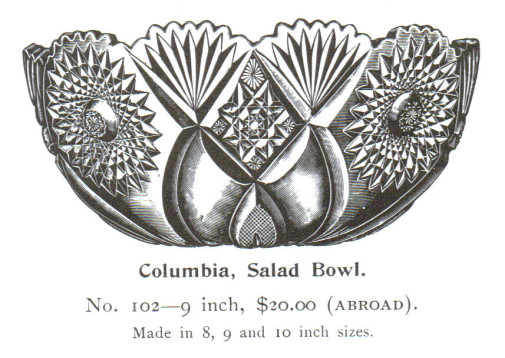

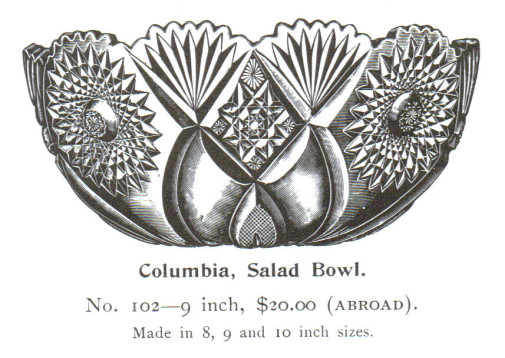

The writer has surveyed several collectors and no one has seen this pattern on cut glass that is signed Hawkes. Also, it should be noted that the pattern has not appeared in any Hawkes catalog that is extant, nor in any other material from the company such as magazine advertisements. When this pattern is found it is usually identified as a product of J. D. Bergen & Company whose 1893 catalog was reprinted by the ACGA in 1999. The following image is taken from this Bergen catalog (p. 9):

Compare the exhibited bowl to the catalog illustration. Bend down so that you can view the former's profile and can readily see its remarkable resemblance to the above engraving. In addition to the "cut and polished plain sections" (tusks), notice the interior fans. It is observed that Bergen always uses 2- (or 3-) ribbed fans while Hawkes uses fans with many more ribs. Note also how the two ribs on the exhibited bowl are extended, almost touching the major hobstars. While the exhibited bowl has U-notches on its rim, which would normally suggest a Hawkes origin, Bergen could have inadvertently copied the Hawkes rim if the company used the published Hawkes patent drawings as its model. Note that the rims in the Bergen catalog are often carelessly drawn, as they are in the above illustration. Because both Hawkes and Bergen varied the cutting on the hobnails of the major hobstars in their respective Chrysanthemum and Columbia patterns, sometimes using single stars, sometimes Brunswick stars, these characteristics can not be used to identify the manufacturer. Conclusion: The exhibited bowl should be investigated further (note 4).

Move over to the case containing the J. Hoare glass window: Bowl Cut in "1614" Pattern. J. Hoare & Company, 1900-1910. 2002.4.54, gift of Frederick Campbell Hovey. This pattern appears in Hoare's 1910 and 1911 catalogs, but this bowl is not marked. That probably means that it was made when the pattern was first introduced and before the consistent use of the trademark. Be that as it may, the bowl is ideally positioned to show how one can identify the use of a "figured" blank, where part of the pattern was in the mold that was used for the item's shape. Such items were considered inferior cut glass by manufacturers such as T. G. Hawkes and A. L. Blackmer. They are rather like a cake made from a Duncan Hines cake mix rather than "from scratch". You can readily see the "figured" nature of the blank by bending over slightly and positioning the reflected image of the overhead light midway up on the bowl's side. Then, moving your head to the right and to the left observe the image of the light as it crosses the mitered bands that form part of the bowl's pattern. The image will "jump" cross those miter cuts that were in the mold. Today many collectors avoid "figured" blanks because, to a degree, they are ersatz cut glass. If this bowl were cut on a plain (i. e., non-figured) blank it might be worth $200 (the pattern is run-of-the-mill), but what is its value as a "figured" bowl? Now consider the nearby Hoare bowl that is cut in the elaborate Arabesque pattern (2005.4.24). Repeat the "image test" and you will see that the interior of this bowl is perfectly smooth (no jumping of the image). Relative to this bowl, answer this: What is the name of the minor motif that appears to be Russian? Nine people out of ten will probably answer "Russian, of course". But look again, the pyramidal stars are boxed in with squares. (These are incomplete because they are located at the edges of the motif.) In spite of the fact that the motif's hobnails are cut with single stars (as in Russian Canterbury, to use a collector's term-of-convenience), and not hobstars, this motif is Persian!

Itinerary: The Post-Brilliant Period

Leave this section of the Crystal Gallery by walking past the Cutting Shop models to the next area. You can return later to examine the extensive displays in the cases on your left and far right. Move to the island case so that it is on your right. Examine the variety of stem- and bowl-shapes in this case which have been cut and engraved by Corning companies: Hawkes, Sinclaire, and Hunt. Not all of the Hawkes ware are signed because the company, on occasion, was using a blue paper label instead of its usual acid-etched trademark, or HAWKES signature, during this period, c1920 to 1960.

In the left-hand corner of the case there is the label: Top, Item 2. Sample Goblet in "Delft Diamond" Pattern. T. G. Hawkes & Company (marked), 1930-1960. 76.4.51, gift of R. L. Waterman. The goblet has been incorrectly identified. Its pattern is Hobnail. Delft Diamond, a renaming of the older Table Diamond pattern, is produced by two intersecting sets of parallel miter cuts. One can clearly see that the cutting on this goblet has the three intersecting sets of parallel miter cuts that are necessary for the Hobnail pattern. Move to the other side of the case, that is, diagonally, so that you can read the label for the prominent row of six water goblets, also a gift from Waterman. Photos of these goblets are shown in Sinclaire and Spillman (1997, pp. 118-122). This particular shape (no. 6015 if with a square foot) is especially attractive although not particularly practical -- the foot is easily chipped. Stemware such as these samples, together with other examples in this case, are not yet of major interest to collectors; consequently, they are often seen on eBay and elsewhere, reasonably priced. They help illustrate the fact that Hawkes was producing quality tableware during these later years of the factory's existence. A seventh example in the no. 6015 series, cut in Hawkes' Eardley Waterford pattern, is available in the Littleshop file.

Do not overlook Item 1, the impressive 15+" plate in Hawkes' Empire pattern that was designed by Samuel Hawkes. It was recently acquired by the Museum (2005.4.49) and is another example of the quality workmanship that can be found on items produced during this so-called post-brilliant period. Lastly, on your right is the label "Glass for the White House" but the only White House glass it contains is Item 6 (97.4.215), a finger bowl that was first ordered by the Roosevelts in 1937. Later in the walkabout we will visit another case that contains White House glassware . At that time we will comment on this pattern, popularly known as "Picket Fence".

Itinerary: The Pre-Brilliant Period (Early and Middle Periods)

Exit the area and walk straight ahead, past the two large island cases, to the window wall where you will find Eddie Murphy's famous cut-glass baseball bat (L.50.4.2003) in its own case. We will use this case as a starting point, and consider some of the cases to the left and right. Meanwhile, while standing in front of the bat you might want to consider it. Barbe (1996) and Spillman (1996b) have provided background information for this showpiece, but Barbe's discussion of the bat's motifs is flawed. Make your own list of the motifs. We have identified no less than eleven. They are listed in note 5, but do not peek!

The third case to the left -- "Early cutting": Observe both the wide variety of motifs and patterns used during the early period, including the curved-miter cut. Note the variations in the color of the glass-metal at this time.

The second case to the left -- "Mid-century cutting": Compare Item 3 (93.4.7), a celery vase cut in the Buckle pattern, to the goblet in this pattern that is shown in the buckle.htm file in Part 3 of the GUIDE. Also, pay particular attention to Item 9, the Fowler compote of 1860 (Barger et al 1981-2). J. Q. Feller, author of the definitive book on C. Dorlinger & Sons (Feller 1988), was unable to obtain permission to use a photograph of this compote in his book, although one is included in the Barger article. Partly because of this unfortunate situation, this item has received relatively little attention and has been somewhat overlooked by Dorflinger enthusiasts. It also has been overshadowed by the more widely known and discussed Dorflinger Guards' vase that the company made the year before. Both of these items are equally important. Fortunately, the owner of the compote has given it to the Museum (2003.4.109), so the story has a happy ending, one that is much better than a mere photograph!

Consider Item 11 . . . Compote Cut in "Star Diamond" Pattern. U. S. A., Sandwich, Massachusetts, Boston & Sandwich Glass Co., 1880-1888. 2005.4.192. The compote's pattern not only looks like Quarter Diamond but it is Quarter Diamond. However, because the manufacturer is known, the company's name for the pattern must be used: therefore, Star Diamond is the correct name (Nelson 1998). Most manufacturers of the day used the generic name Quarter Diamond.

The next case is immediately to the left of the baseball bat -- "Rich Cut glass". Item 8. Lamp Cut in "Russian" Pattern. U. S. A., New Bedford, Massachusetts. Pairpoint Manufacturing Company, glass probably from Mt. Washington Glass Company, 1880-1900. 2004.4.57, gift in part of Bill Johns. The pattern's identification is incorrect: It is not Russian. Although generically known as Star & Hobnail, in this case -- as in the case of the Boston and Sandwich compote -- the manufacturer is known (or suspected), so the company's pattern name, pattern No. 60, must be used. Notice the curved crack in the lamp's globe. Has this damage been treated to prevent further deterioration?

Seventh case to the right of the baseball bat -- "Presidential glassware": Examples from White House table services of the past, including the Lincoln pattern (from 1861), the Russian pattern (from 1891), and the Venetian/White House pattern (from 1938). Item 7. Water Goblet from a White House Service. U. S. A., Corning, New York, T. G. Hawkes & Company, 1938. 51.4.534, gift of T. G. Hawkes & Company. This goblet is from the service ordered for the White House by President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt. Joseph Sidot engraved it. Note that although no pattern name is provided, it was reported as early as 1982 that Hawkes was using the name "Venetian" for the pattern at the time the table service was ordered (Spillman 1982, plate no. 9). Two years later Waher (1984, p. 96) reproduced a photograph of a "Piece of the State Service of the White House" as displayed at the Lightner Museum. The "piece" is a duplicate of the goblet exhibited here, and Waher also reports that the pattern is called "Venetian". Finally, by 1989 Spillman could state unequivocally that "The Roosevelts chose a pattern that Hawkes had marketed as 'Venetian', but which the company renamed 'White House'" (Spillman 1989, p. 121). In spite of this evidence, the Museum uses neither of these pattern names on its labels.

Spillman also shows a White House photograph of tableware in this pattern/shape that were ordered from Hawkes repeatedly from 1937 to 1955 (Spillman 1989, p. 132). Included are goblets, wines, sherries, finger bowls, saucer champagnes, and cordials. Only the first four of these items were engraved with a version of the Great Seal. Apparently the Museum has only two examples from these years: this goblet and the finger bowl that we saw earlier. Spillman suggests that the blanks were probably made by the Tiffin Glass Company, Tiffin, OH using a lead-glass formula provided by Hawkes (most recently discussed in Spillman 1996a, p. 248).

The pattern on the White House tableware is an old one, having been cut by Dorflinger before 1900, while the shape of the stemware, with its bucket bowl and angular knop, looks back in time to British styles of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. At least two companies other than Hawkes produced stemware that matches the item under discussion: Pairpoint (and its successor Gunderson-Pairpoint) of New Bedford, MA, and the Seneca Glass Company of Morgantown, WV. In addition, Sinclaire and Steuben are said to have cut the pattern. Hawkes marked some, but not all, of its tableware with its acid-etched trademark from c1930 to 1955, but the company also used a paper label. Both Pairpoint and Seneca used paper labels exclusively. Sinclaire-cut items may be signed, but any from Steuben probably are unsigned. The pattern is also an international one, adding to the confusion surrounding the identification of manufacturers. Items in color (cut-to-clear) are especially likely to be foreign imports. Val St. Lambert of Belgium, where the pattern is called Florian or Steinmann, is one such source, although colored items from Sinclaire and Steuben, as well as Pairpoint, must also be considered as possible manufacturers of this popular "Picket Fence" pattern.

The Pairpoint Corporation (and Gunderson-Pairpoint) identified this tableware as pattern No. 33 on shape no. 5000 (Nantucket) (Avila 1968, pp. 121, 194), while Seneca called its "line" cut no. 859 (Renaissance) on shape no. 908 (Page and Fredericksen 1995, p. 53). The Pairpoint companies made this stemware from as early as the mid-1920s to the mid-1950s. While it is not known when Seneca first introduced its version, it is found in the company's catalogs as late as 1970.

It should be emphasized that some examples of this pattern/shape found today match the exhibited goblet exactly, with only the engraving omitted. However, other examples are found where the cut pattern is raised slightly higher on the bowl -- that is, more centered -- than it is on the exhibited goblet (probably because no engraving was anticipated). On a set of six unsigned saucer champagnes that recently came to light on Market St., Corning, the cut pattern occupies only the lower half of the bowl, matching the saucer champagne shown in Spillman 1989 (p. 132). Plenty of room has been left for an engraving should a customer subsequently wish to order one. Perhaps this set -- which is listed in the Littleshop file -- is waiting to hear from the White House!

We will now briefly visit two groups of cases to which you can return later: (1) Return to the baseball bat, then walk to the left, along the window wall, noting the cases labeled "Americo-Bohemian glass" and "Souvenirs for America", past several cases with lighting fixtures, and ending at the unmarked wall case that contains cut and engraved glass from the New England Glass Company and Bakewell, Page & Bakewell. The collectors' period of American cut and engraved glass really begins here. (2) For the second group of cases continue along the window wall until you reach the Frederich III engraved plaque in its own case. Beyond this point you will find several cases of 18th and 19th century foreign cut and engraved glass that show the influence individual countries have had on the development of the American cut-glass industry during the 19th century. Mark especially the following cases for a return visit: "Apsley Pellatt", "Sulphides", "French glass", "Anglo-Irish glass", and "Desserts". Return to the Frederich III plaque and notice the case of "Biedermeier glass" to the right. These examples anticipate the Splitting the Rainbow Exhibit. Item 5 clearly shows its interior casing of red glass, a feature that is not always so easily identified. (Error: Items 3 and 4 have been reversed.)

Turn about-face and return to the curved inner wall, pausing at the large island case, "Glass in the 18th and 19th Centuries", that contains a large two-piece Bohemian vase and stand, Item 22 (2004.3.46). Observe that this item is made of colorless, non-lead glass that has been internally cased with red glass. Three other items in this case are worthy of note: Item 6, Dessert Stand (83.2.27 etc.) with its individual glasses, all slice-cut (also called edge-cut), the technique/style that preceded the use of steam-power in cutting; Item 9, Wine Urn (50.2.59), also slice-cut and in a pattern that matches the pair of Anglo-Irish covered urns that are in the Littleshop file; and Item 7, Pineapple Stand (2005.2.4) which has an impressive display of pillar cutting.

Turn around and enter the Study Gallery. Proceed to the third bay on the left and stop in front of Cabinet 27 (which is marked). Third shelf: We are now in a position, literally, to see an example of the Persian variation of the Russian pattern, as promised. It is on the free-form bowl on the right, behind the dish that is cut in horizontal prisms (step-cutting). The bowl's hobnails have 12-pt hobstars. Because this item can be attributed to C. Dorflinger & Sons, one must use the pattern name that Dorflinger gave it: Brilliante. While here notice the entire, unlabeled collection, especially the Top shelf with its trio of Blackmer items that are pictured in Revi (1965, p. 65). The tall tumbler and the champagne glass are both cut in the company's Columbia pattern, but the pattern on the vase, which can be confirmed as a Blackmer product, has not yet been identified. The name Constellation, assigned to it by Revi, is incorrect. (Constitution is Blackmer's name for a different pattern.) Second shelf: On the left is a White House goblet cut in the Russian pattern and engraved with the Great Seal. In front of it is a goblet engraved with the letter H. Its cut portion is the same as that on the White House's Lincoln service. It probably dates from this period (c1860-80) and possibly was also made by the Dorflinger Glass Company. It is pictured and discussed in the GUIDE.

Before exiting, enter the bay opposite and find Cabinet 65. Notice the Scent Bottle (2004.2.4) on Shelf 4. It illustrates the close connection between the elaborate English cutting of this period (1820-30) and the similar cutting that was undertaken in this country, for example at Bakewell's factory in Pittsburgh, at least on important items such as President Madison's decanter of 1816 (L.136.4.85) which is found in the case of "Presidental glassware" previously visited. The cologne is in two parts -- the central bottle lifts out. Unfortunately, this item arrived too late to be included in the writer's account of scent bottles made in the form of a crown (see the foreign6.htm file in Part 1 of the GUIDE).

Exit the Study Gallery, and visit the island case labeled "19th Century European Glass" which is kitty-corner from the Study Gallery. Item 32 is the famous Fritsche Ewer (54.2.16). It has been placed on the far right and is easily overlooked. Then continue along the curved wall to the Crystal Gallery where you started, pass by it, continue on, and exit. Turn left at the yellow "Tour continues" sign and enter the West Bridge gallery and its exhibit, Splitting the Rainbow: Cut Glass in Color.

Itinerary: The Splitting the Rainbow Exhibit

You will have to number the unnumbered cases yourself, from the first one on your left, no. 1, clockwise around the gallery to the last one, no. 17.

Some of the pieces on display were made of one layer of transparent colored glass, but most were created using two or three layers of glass -- casing or layering colored glass over high-quality clear glass to create a "blank" (Spillman 2006, p. 5).This quotation prompts us to establish the following four "house rules" with which we should all be in agreement:

(1) "Cased glass" is a term of choice. It is used for all of the layered examples in the exhibit. Occasionally the term "overlaid glass" is used; when it is, it is used synonymously with cased glass. This may not, however, be true elsewhere. "Plated" was a term used for cased glass during much of the nineteenth century; today it is considered archaic.

(2) "Layer" is a thickness of glass "spread over a surface" according to the dictionary. But here it is also the surface itself! That is, any glass object can be considered to be a layer. This sounds strange, but it arises from the fact that, in the so-called cup method of casing, all of the layers of glass involved -- including the object itself -- begin life as individual gathers of molten glass. Thus, a colorless wine glass can be thought of as a glass of one layer.

(3) "Colorless". How this term is used is even stranger than that of layer. In layering, colorless glass is regarded as if it were colored glass! Therefore, our colorless wine glass is a glass of one color as well as a glass of one layer.

(4) "Color". Colors are not standardized, and their descriptions are, to a degree, subjective. Therefore, each part of the spectrum -- red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet -- will be found with a wide gradation of hue. For example, blue can range from aqua to turquoise to a deep blue. Different observers will often describe a particular color differently; one man's yellow can be another man's amber.

We can now discuss layers of color, from one to as many as four, using the objects exhibited.

The tall pitcher in nearby Case 9 appears to have two layers of color, but, in fact, there is only one layer because this glass, amberina, is homogeneous. As stated in AN ILLUSTRATED DICTIONARY OF GLASS this is "a type of art glass featuring varying colours shading (usually from the bottom of a piece to the top) from light amber (straw) to rich ruby. When an object (mould-blown or free-blown) is first made, the overall colour is amber, but when part is reheated that part (due to particles of gold in the metal) develops the ruby colour ... and if reheated longer it develops a purple (fuchsia) colour." (Newman 1977, pp. 22-3). This color-change is three dimensional. Notice that the deepest color is not only at the top of the pitcher but it also penetrates into the pitcher to some depth -- best seen on individual hobnails. This third dimension is usually impossible to observe in a photograph. Thus, the pitcher is also "one layer of transparent glass" but, admittedly, the color change can be so great that the transparency of the glass is strongly affected -- note the item's handle. This pitcher appears in public and private collections with some regularity, where it is usually incorrectly labeled as being cut in the Russian pattern. You can see that the pattern is the generic Star & Hobnail pattern, but, because the pitcher ia attributed to the New England Glass Company, it is necessary to use that company's name for the pattern. As indicated on the pitcher's label this is Hob & Star.

A third example of a single layer is provided by President Lincoln's wine glass in Case 5. Its glass is green, through and through. The glass's label, however, also refers to two sizes of wine glasses at the White House in this pattern that are "red". But these glasses are not red in the same way that the exhibited glass is green, as explained in the following section:

Internal Casings: Unfortunately, there is no red Lincoln glass in the Museum, but one can find a fine photo of one in Spillman's 1996 book (p. 238). It represents one of the two sizes of red wines mentioned on the green glass's label -- each has a red bowl and colorless stem and foot. The bowl appears to be solid red, but it is not. It is internally cased with red glass. By using an internal casing much less red glass -- which was expensive to make -- was used than would have been the case had the bowl been made of solid red glass. Also, the glasscutter Thomas Matthews has pointed out that colored lead glass is a harder substance than colorless lead glass, and it is, therefore, more difficult to cut (in Boonstra 1995, p. 6). Because the casing is internal and is, obviously, not cut, this problem is avoided. H. W. Woodward, in his brief history of the glassmaker Thomas Webb & Sons (U. K.) mentions another reason for red casings: "A piece of thick ruby glass would look much darker [than cased glass] and semi-opaque, and not such an attractive color." (Woodward 1984, p. 50). These are all reasons why red glass was often used as an internal casing during the nineteenth century. (Compare the large two-part Bohemian vase we visited earlier). While internal casing is sometimes described as rare, it was, in fact, used as a standard technique in the United States thoroughout the latter half of the nineteenth century.

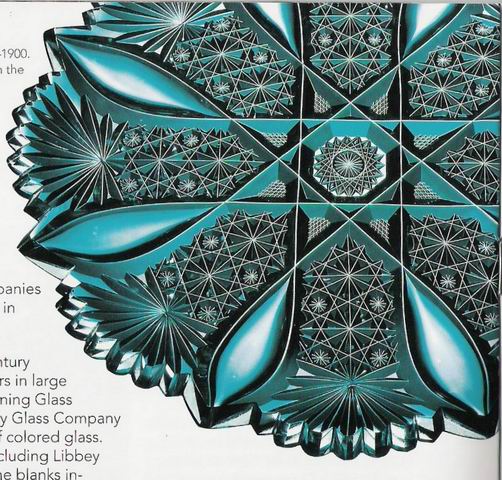

Without a laboratory setting it is difficult or impossible to see the colorless layer on a wine glass's bowl that has been internally cased with color. However, on more robust items such as pitchers, bowls, and plates, the colorless layer is thicker and is more visible. A plate in a striking shade of green in Case 11 (2003.4.26) provides a good example, together with an interesting problem. But first a description: This item appears to be made of glass of a single color, but based on what we have experienced, we have to ask: Is this a solid color or does the plate have a casing? For the answer, view the plate edge-on. You will readily see that it has a very thin casing of color on a thick, colorless layer, and that the casing is internal, that is, it is on the inside (the uncut side) of the plate. The color is an interesting one: it has been described variously as aqua, turquoise, and green. A complete description of the item might read: "Plate of colorless lead glass, cut in the Grecian pattern by T. G. Hawkes & Company and internally cased in green". The word "internally" is perhaps redundant; the casing could not possibly be external.

The following image of the plate, unedited, is taken from Spillman's exhibition article. It shows something that is completely unexpected, apart from a not-too-surprising change in color from green to blue. This change is fairly frequently observed in photographs unless great care has been taken in the photo-printing process. At first glance the image suggests that the plate is cased externally and has been "cut-to-clear" to use the phrase often applied to such two-color items, as will be discussed shortly. By observation we know that this is not the case. Under normal viewing conditions, such as those in the West Bridge gallery, the plate shows only green, front and back. There are no colorless areas (apart from the plate's rim) such as these that are found only on the image: on the "pea pods" and around the central Brunswick star; and there are no colorless miter cuts which here in the image so effectively show the Russian motif that is part of the Grecian pattern. What has happened?

The photographic setup obviously included a strong light to illuminate the plate's cut side, and a camera that was placed on the opposite side of the plate, viewing its uncut, cased surface. It is assumed that all three objects: camera, plate, and light source were aligned roughly in a straight line so that the light fell perpendicularly onto the cut surface. As a result, any part of the cut surface that was perpendicular to the rays from the light source had its color "drained away". This explains all of the colorless areas and lines, including the latter which were cut by the V-shaped miter wheel. Because the sides of all of the V-cuts do not present surfaces that are perpendicular to the light source, they show color. The foregoing is an intuitive argument. It needs to be backed up with an explanation from a physicist, a "proof" that is complete with diagrams of the rays of reflection, refraction, and transmission, and perhaps even with an equation or two!

While special photographic techniques are often used to highlight an object's unusual attributes and particularities, they should always be mentioned. Here the reader -- of Spillman's article, for example -- is left with a completely false impression as to the true appearance of the plate. It should be re-photographed.

External Casings: The most popular antique colored cut glass found today, based on the numerous examples one sees in the marketplace, are glasses with external casings of color, where the cut or engraved pattern has been cut through the colored casing, revealing the layer of (usually) colorless glass underneath. Collectors call this glassware "cut-to-clear". It is also the most popular type of colored glass in the exhibit, judging from the numerous examples found mainly in the following cases:

Case 7: Red cut-to-clear. All items except the claret jug.Case 8: Red cut-to-clear. All items.

Case 10: Green cut-to-clear. All items. The Quaker City pinwheel bowl (89.4.50) is not unique. Two exact duplicates are known: One was exhibited at the Museum of American Glass in 1991 (Taylor 1991, [p. 2]), and the other is owned by a friend of the writer's. It is shown in the colored3.htm file in Part 1 of the GUIDE.

Case 11: Turquoise cut-to-clear. All items except the green plate.

Case 13: Blue cut-to-clear and amethyst cut-to-clear. All items except the nappy.

Case 14: Amethyst cut-to-clear. All items.

Cases 15 and 16: Most, but not all, of the wine glasses are cut-to-clear in various colors. In viewing colored wine glasses it is always a good idea to check the bottom of the glass's bowl, on the inside. (Stand on your toes if you have to!) Doing this you will be able to check the glass's external casing as well as determine if the glass has either an internal casing or is a bowl of solid color, but this inspection can not distinguish between these two possibilities.

In cut-to-clear glasses you will usually find one of the following three characteristics in the interiors of the bowls, as shown by the glasses in Case 16:

- Glasses in the center: A colored area that contains a small clear area (size varies). This is an example of what one usually finds. C. Dorflinger & Sons.

- Glasses to the left: An area of solid color with no clear area. Three glasses are color-cut-to-clear, the fourth has a solid amber bowl. Possibly Dorflinger.

- Glasses to the right: No area of color on two glasses. (The third glass, not cut-to-clear, appears to have a small colorless area in spite of the fact that it has two casings.) L. Straus & Sons, probably on blanks from Baccarat.

Color-On-Color: There is no reason why a colored layer can not be cased onto another layer of colored glass. A fine example is the remarkable bowl by Leon Ledru in Case 2. The bowl is green cut-to-amber. It remarkable because its design is very advanced for the period, 1897-1901. Much more typical of this period is the vase that contains a sulphide of Queen Victoria in Case 3 (71.2.58), a souvenir produced by Stevens & Williams to mark the 50th anniversay of the Queen's coronation in 1887. The vase is pictured in Stevens & Williams' pattern-book and reproduced in Hajdamach (1991, p. 283) who also shows a colored photograph of an identical specimen (p. 253). The author does not mention colored casings, only the general statement that the vase, called "Queen's Head" in the pattern-book, is "amber". But one can see that there is acually a reddish amber casing cut-to-yellow. The two-color wine glass next to the vase is also assumed to be an example of color-on-color. It too is documented in print as a Stevens & Williams product (Williams-Thomas 1983, p. 67), but, unfortunately, Williams-Thomas does not analyze the glass. In writing about this and other colored glasses illustrated in Williams-Thomas's book, this writer earlier assumed that this wine glass has two layers of color, amber cut-to-yellow (in the foreign6.htm file in Part 1 of the GUIDE). He sees no reason to change this assumption, but, as in the case of the vase, one must consider the possibility that each color has been cased onto an intermediate layer of colorless glass. The writer feels that this is unlikely, however. The English seem to have developed considerable experience in the use of transparent color-on-color during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Opaque color-on-opaque color is also possible, of course. There is no example in the exhibit (but you can find one -- a vase that is assumed to be Chinese -- in the colored3.htm file in Part 1 of the GUIDE). Here we have only a couple variations: A cologne bottle in Case 1 that has opaque green glass cut-to-clear (54.3.51) and another cologne in Case 6 where an opaque white casing has been cut-to-transparent blue glass (84.4.225).

Three Layers, Two Colors

With three layers and two colors one is looking at a single color, applied twice to an intermediary colorless layer. An Oreo cream sandwich in glass! At first glance the claret jug in Case 7 appears to be an example of this, but as we shall see the jug tells us a different story. However, there is a basket in the Texas Cookbook that does qualify. Its owners report the "the interior and exterior of this basket is cranberry with clear glass between the layers of cranberry." (Lone Star Chapter 1994, p. 397). The basket is a model with an integral handle. It was patented in 1884 by John Hoare (pat. no. 296,691), so it is reasonable to assign this item, which is cut in the Persian variation of the Russian pattern, to John Hoare's company.

Two other examples: A friend of the writer's has written that he has a wine glass with a construction that is identical to that of the basket's. It is cut in the generic cane pattern. One might also add, but with some reservation, that the pair of wines in the back row of Case 15 represent three layers and two colors, but here there is some uncertainty.

In this category the top and bottom of the Oreo cream sandwich have different colors, but still with a colorless layer in-between. While the claret jug in Case 7 (99.4.94) appears to have an interior casing of red and an exterior casing of the same color, one can obtain a cross-sectional view that indicates that this is not the case. To do this, face the case and position yourself at its left end. Then, kneel! In this position you can look through the base of the jug. You will see a thick, colorless layer with a thin, interior casing of red immediately above. Re-focus your eyes on the exterior of the jug while remaining in this same, dignified position. You will see that the exterior casing is very dark, almost black, but that its edges show that its color is amber, which is quite a surprise. One would have expected red. Thus, the claret jug can be described as Claret jug with an interior casing of red and an exterior casing of amber cut-to-clear in the Venetian pattern by T. G. Hawkes & Company . In the caption that accompanies a full-page color photograph of this jug in her book on Hawkes, Spillman (1996a, p. 54) mentions only that this item consists of "cased cranberry over colorless glass", which obviously refers to the internal casing. There is no mention of an external casing.

Unfortunately, this claret jug is cracked. Move to the right and mentally drop a perpendicular from the jug's handle to its base. The crack can be seen about an inch to the left, running from the base upward. It is not mentioned in the aforementioned photograph in Spillman's book. While on your way to the next exhibit, consider what monetary value you would place on this damaged item. (The writer does not have exceptional eyesight; he saw the jug before it was given to the Museum.)

A second example is the "legendary" Borrelli three-handled loving cup in Case 9 (Is this a loan? No identifying number is given.). Having come from New England and knowing something about the loving cup's history, the writer feels that "legendary" is justified. The cup was the subject of much speculation for many years. For our purpose it is interesting to note that there was mention of it in Bill and Louise Boggess' 1992 book COLLECTING AMERICAN BRILLIANT CUT GLASS in the following single sentence: "A collector has a loving cup in ruby-cut-to-blue[-cut]-to-clear in the Crystal City Pattern signed Hoare" (p. 41). Because this is a Boggess statement, errors are not surprising. Two years later the cup appeared at the 1994 convention of the ACGA, perhaps its first "public" appearance. Its photograph was published, along with several other colored items, in a special issue of The Hobstar. No specific color is mentioned, only the ambiguous statement: "Full colored glass body" (Boonstra 1995, p. 12). One concludes that the ACGA believes that the loving cup is made of one color.

In the fall of 2003 the loving cup was featured, in color, on the cover of The Hobstar (Vol. 26, No. 4, December 2003). A brief note about it, based on information supplied by its current owner (the Borrelli estate) confirms elements of my recollection of its early history as described above. Unfortunately, the loving cup is not analyzed by the individuals involved in this display, and one is left with the impression that all involved believe, erroneously, that the cup is made of solid, red glass.

There is the following statement in Case 9: The loving cup, red over blue, is unique. But a more complete description of the cup is left to the viewer. There is no mention of a signature, and the manufacturer of the sterling silver mounts is not identified. The writer suggests the following description, but he welcomes alternate suggestions. This item is the most difficult one in the exhibit to describe accurately and completely: A vase with sterling silver mounts, including three handles, that provide a loving cup. A colorless glass body with an interior casing of red and an exterior casing of blue cut-to-clear in the Crystal City pattern by J. Hoare & Sons. To locate the blue casing, which is elusive, view the cup from the inside. Look through the two casings in an uncut area near the top, and you will see a bluish color. Also, view the pillar cutting from the inside. The blue casing is evident as a median running along the curved "rings". In addition, the blue casing remains on the hobnails in the cane motif which appear dark and of an indeterminate hue. Otherwise, almost all of the blue casing has been removed. Yet enough remains to prevent the colorless layer from becoming visible. As in the case of the claret jug, this is the main reason for external casings in objects such as these.

The so-called Bohemian style in America, 1845-1875, often used opaque colors in three layers and three colors. Because double external casings were used, this glassware is sometimes confusingly called "double overlay". Barlow and Kaiser, the Boston & Sandwich specialists, use this term to describe several examples in their guide to "cut ware" (Barlow and Kaiser 1999). The lamp font in Case 6 (79.4.101) is the exhibition's example, probably made in the Pittsburgh area, 1860-1875. It consists of opaque red-cut-to-opaque white-cut-to-colorless glass.

Double external casing of transparent colors is also possible. This seems to be an English specialty and is not represented in the exhibit. One example ("maker unknown") was in the Museum of American Glass's 1991 exhibition, an engraving that consists of green cut-to-pink-cut-to-colorless. There are also several examples by Stevens & Williams, all goblets, in the foreign6.htm file in Part 1 of the GUIDE.

Case 5. Exhibition Vase with Four Layers of Glass. U. S., Cambridge, Massachusetts, blown by William Leighton for the New England Glass Company, about 1848-1858. 93.4.9. This vase is said to have cost $200 to make. It would have taken a skilled worker three months to earn this much money. This remarkable vase was cut to represent a lily -- "there is the green bulb, the white leaves, red center, then a clear flint portion, and rising above all a red top" (William Leighton, Jr. as quoted in Spillman 1996c, p. 150). Take the time to find each of the vase's external layers -- opaque green over opaque white over transparent red over colorless -- and observe that the first two layers cover only slightly more than the bottom half of the vase. The additional use of gold to "gild the lily" is quite literally true in this case! This item is the corner stone for the "layered" approach to color in American cut glass.

Colored parts, such as handles, stems, and feet are often applied to colorless glass to add color. The bowl with gilded decoration (2004.4.72) in Case 12 has had prunt-like blobs of yellow glass, subsequently faceted, added to the colorless bowl.

In Case 13 the H. C. Fry Glass Company has permitted a blob of blue glass to suffuse slightly in a gather of colorless glass to produce two-colors in a nappy that has a matching blue handle (98.4.270), while in Case 17 an experimental plate (private collection), cut in the Strawberry Diamond and Fan pattern, was made with very little mixing of gathers of red, blue, green, and colorless glass, giving a startling and novel effect.

A virtual jury has received the following evidence in Dorflinger vs Others:

Case 2. Vase. Belgium, Liege, Val St. Lambert, 1900-1915. 79.4.305, gift of Katheryn Hait Dorflinger Manchee. This pattern is also said to have been made by the American firm of C. Dorflinger & Sons. Ever since 1998 when four catalogs from the Val St. Lambert company were reprinted by the ACGA in the publication CRISTALLERIES DU VAL SAINT-LAMBERT, it has been recognized that this vase was produced in Belgium and not in this country by C. Dorflinger & Sons. The label is correct except for the last sentence which can, and will, be interpreted by some viewers as suggesting that Dorflinger also made this item. However, there is absolutely no evidence that this is so. That Dorflinger made this vase was given credence by the Museum in 1982 in a Knopf series on antiques, and repeatedly since then in books by Bill and Louise Boggess where erroneous identifications are all-too-common.

Mrs. Manchee, the donor, inherited this vase through her first husband who was a grandson of Christian Dorflinger. She obviously believed that it was made by Dorflinger when she gave it to the Museum in 1979. However, she seems to have overlooked the possibility -- as did the Museum -- that the vase could have been acquired by the Dorflinger company for the purpose of studying it as an item-of-interest. This was a common practice of glasshouses at this time. It should, additionally, be noted that Mrs. Manchee herself might have had some doubt about the origin of the vase. It is not mentioned in her three-part article on the Dorflinger company that was published in The Magazine Antiques in 1972, nor is it (or its pattern) included in Feller's 1988 book on Dorflinger, even though Mrs. Manchee worked closely with Feller for several years during the 1980s (Feller 1988, p. xi). In 1982 the Museum published the vase and based the description of it partially on information supplied by Mrs. Manchee. Included is the claim: "The piece illustrated was cut by C. Dorflinger & Sons of White Mills, Pennsylvania" (Spillman 1982, item no. 330). This is undoubtedly the primary source of the misinformation about this vase that has circulated during the past twenty-five years, and which continues to circulate today. The vase, usually in this green cut-to-clear version, regularly appears on eBay, almost always with a Dorflinger attribution. Other versions in red cut-to-clear and in blue cut-to-clear, as well as colorless examples, have also been reported.

Because no documentation exists to support the claim that the vase was ever made by Dorflinger and because individuals are harmed by the erroneous information stemming from its earlier claim, the Museum has an ethical responsibility to either not mention Dorflinger on its label or, better yet, to repudiate its statement of 1982. As matters now stand, the offending sentence will continue to suggest that copies of this vase can be legitimate products of C. Dorflinger & Sons, and this is a deception. In 2001 this occurred: A green cut-to-clear 22" tall vase was sold as Dorflinger on eBay by a ACGA dealer for $2,550. However, three years later another green cut-to-clear example, this time 14" tall, failed to sell; it had a starting price of $1,195. In addition, auctioneers who routinely described such vases as "Dorflinger" in the past are now more circumspect. Perhaps the truth is being heard. (See the dorflinger7.htm file, section 3, in Part 2 of the GUIDE for further details on the eBay auctions.)

In 1985 and 1986 Mrs. Manchee, who died in 1991, again distributed cut glass from her Dorflinger collection, this time choosing two lesser-known museums: the Fashion Institute of Technology and the New Orleans Museum of Art. She had previously given items to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the High Museum in Atlanta, and the Brooklyn, Newark, and Cleveland Museums, as well as to the Corning Museum of Glass (Feller 1988, p. 131).

The two new museums received individual ice-cream plates cut in an elaborate, but so far unknown, pattern that Mrs. Manchee assumed was designed and made by Dorflinger. However, evidence has gradually accumulated during the past few years that these plates probably originated with John S. O'Connor at his American Rich Cut Glass Company. It would have been natural for O'Connor, a long-time Dorflinger employee and a personal friend of Christian Dorflinger, to have given the dishes to him as a gesture of esteem, perhaps as part of an ice-cream service to celebrate a birthday or other special occasion. There is no doubt that Dorflinger used the dishes for more than ice cream, however. The company's Sonora pattern is a simplification of this assumed O'Connor pattern (to which the name "Vesica" has been assigned as a matter of convenience). As in the case of the green cut-to-clear vase, above, the pattern in question does not appear in any collection of Dorflinger material -- catalogs, advertisements, and the like. And, as in that case, there is no mention of these plates in Mrs. Manchee's writings or in Feller's book. Therefore, it appears that we have another case of "Dorflinger" glass not being what it seems to be. But in this situation the blanks that were used for the dishes most likely did come from the Dorflinger company. (See the oconnor6.htm file in Part 2 of the GUIDE for further discussion.)

Case 10. Vase. "Fern" Pattern. U. S., White Mills, Pennsylvania, C. Dorflinger & Sons, 1895-1910. 98.4.641, gift of Walter Poeth. If one counts the plates in the "Vesica" pattern described above, then this is the third example of a supposedly Dorflinger item (pattern and blank) that is more likely to have been made by some other company, presently unknown, than by the manufacturer in White Mills. As in the previous examples, the item in question descended in the Dorflinger family, this time as a nearly 14" tall green cut-to-clear vase, through the descendents of Louis Dorflinger, one of Christian's three sons. The exhibited vase is a little brother to the Dorflinger example which has been reproduced in Feller 1988 (p. 152).

A third example of this vase, in apricot cut-to-clear, also exists. It too is found in Feller (p. 177). Both of these vases are also pictured and discussed in an article by Feller and Dorflinger that was published in The Magazine Antiques in 1988. Unfortunately, in none of this material is there any documentation that these vases were made by Dorflinger. Nevertheless, Feller is emphatic. About the apricot vase he writes: "The color is unrecorded, but the blank and pattern are undisputably Dorflinger" (p. 177). In regard to the green vase he remarks that it sold for $7 about 1900. But he describes that item only as a vase in the "Fern" pattern. Becuse there are four different fern patterns in the Dorflinger catalog, including Engraved & Fern, and none are identical to the pattern on the vases, this information does not support Feller's contention.

The writer has a special interest in the apricot vase because he owned it for more than two years. It was purchased from Red Velvet Antiques at a Boston, MA antiques show on 19 Nov 1983 for $225. At no time did the writer regard it as being made by Dorflinger, and neither did the seller nor the person who eventually bought the vase from the writer. Additionally, the vase was discussed with other, interested parties during this period. None regarded a Dorflinger origin as more than a possibility and a rather remote one at that. Now that three of these vases are known -- all identical except in size and color -- it is even more likely that they were not made in White Mills, since there exists no advvertising or catalog material that would link this "line" to C. Dorflinger & Sons. In addition there is no Dorflinger pattern match and no matching Dorflinger blank. The similarity between one of the Fern patterns in DORFLINGER LINE DRAWINGS, a 1994 publication of the ACGA, and the pattern on these vases suggests that possibly the green vase was used as the model for one of the Dorflinger fern patterns (p. 65), but even this is not an exact match. The writer concludes with the observation that the fern fronds on the vases look more like feathers than ferns.

Our virtual jury has returned with these verdicts:

In an unusual added note the jury recommends that all involved museums re-examine any gifts they may have received from Mrs. Manchee during the '70s and '80s -- gifts of cut and engraved glassware that were originally attributed to C. Dorflinger & Sons. And, in a more jocular vein, the jury suggests that an appropriate pattern-name for the design on the "fern" vases might be "Horse Feathers"!

NOTES:

The Corning Museum of Glass maintains a Glass Object Data Base that contains information that is additional to what is found on an object's label. Although this computerized data base is not available to the public, staff members at the Rakow Research Library will look up information for you. But you will have to provide the item's accession number, which is one reason why these numbers are included in this file.

1. In this respect the present report is an update of labeling errors found in July 2005 and previously reported (see the Corning 1a file).

2. John Kohut found the exhibited door panel, which is one of several, and has discussed his discovery in two articles: Kohut 2003a and 2003b. In neither article is the Russian pattern mentioned, and the Brunswick star is called a "flat hobstar".

3. The wines were originally incorrectly identified by Jane Shadel Spillman, Curator of American Glass, according to the Museum's Annual Report 1998 (p. 27), where they are said to be cut in the Russian pattern. This error was subsequently corrected -- as currently indicated on the Museum's label for the glasses where the pattern's name is correctly given as Persian. However, in a recent article that introduces the 2006 exhibit, Splitting the Rainbow, Spillman again misidentifies the pattern, this time calling it Star and Hobnail (Spillman 2006, p. 5).

4. Such an investigation requires preparing a provenance or history of the item based on documented evidence, including information that the seller and/or buyer might consider confidential. All-too-often provenances are fragmentary and of little practical use, but it is, nevertheless, helpful to assemble as much reliable information about the item under investigation as possible.

5. The cut-glass motifs that are found on Eddie Murphy's baseball bat are as follows: sharp diamonds; deep prismatic rings; flutes (panels); notched flutes (panels); shallow prismatic rings; 16-pt hobstars with 8-pt Brunswick stars on the hobnails; strawberry (or fine) diamonds; cane; hobnail; and 7-ribbed fans.

Barbe, W. B., 1996: Baseball trophy exhibits Dorflinger virtuosity, The Glass Club Bulletin, No. 179, pp. 5-7 (fall/winter 1996).

Barger, Helen, Sheldon Butts, and Ray LaTournous, 1986: The Dorflinger Guard presents, The Glass Club Bulletin, No. 136, cover and pp. 3-4 (winter 1981-2).

Barlow, R. E. and J. E. Kaiser, 1999: A GUIDE TO SANDWICH GLASS: CUT WARE, A GENERAL ASSORTMENT AND BOTTLES. Schiffer, Atglen, PA, n. p.

[Boonstra, Nick, ed.], 1995: American cut glass in color, The Hobstar, Special edition no. 1, Feb 1995, 20 pp.

[Cassel, Chet, ed.], 1982: [Colored cut glass issue], The Hobstar, Vol. 4, No. 9, 8 pp.

Feller, J. Q., 1988: DORFLINGER. Antique Publications, Marietta, OH, 375 pp.

Feller, J. Q. and D. J. Dorflinger, 1988: Dorflinger's colored glass, The Magazine Antiques, Jul 1988, pp. 142-51.

Hajdamach, C. R., 1991: BRITISH GLASS, 1800-1914. Antique Collectors' Club, Suffolk, UK, 466 pp.

Kohut, John, 2003a: John Hoare's architectural cut glass, The Glass Club Bulletin, No. 197, pp. 8-12 (autumn 2003).

Kohut, John, 2003b: John Hoare's architectural cut glass, The Hobstar, Vol. 27, No. 3, cover and pp. 16-19.

Lone Star Chapter, 1994: COOKING WITH CLASS, DINING ON GLASS. American Cut Glass Association, Carrollton, TX, 414 pp.

Nelson, K. J., 1998: Introduction and The Boston & Sandwich Glass Company trade catalog, c1880, The Acorn, Vol. 8, pp. 40-101.

Newman, Harold, 1977: AN ILLUSTRATED DICTIONARY OF COLOR. London, 351 pp.

Page, Bob and Dale Frederiksen, 1995: SENECA GLASS COMPANY, 1891-1983: A STEMWARE IDENTIFICATION GUIDE. Replacements, Ltd., Greensboro, NC, 104 pp.

Revi, A. C., 1965: AMERICAN CUT AND ENGRAVED GLASS. Nelson, New York, 476 pp.

Sinclaire, Estelle and J. S. Spillman: THE COMPLETE CUT AND ENGRAVED GLASS OF CORNING (Revised edition), Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, 478 pp.

Spillman, J. S., 1982: GLASS TABLEWARE, BOWLS & VASES. New York, 478 pp.

Spillman, J. S. 1987: WHITE HOUSE GLASSWARE. White House Historical Society, Washington, DC, 148 pp.

Spillman, J. S., 1996a: THE AMERICAN CUT GLASS INDUSTRY. Antique Collectors' Club, Suffolk, UK, 320 pp.

Spillman, J. S., 1996b: Cut glass salute to baseball hero is a hit with visitors, Corning Museum of Glass Newsletter, winter 1996, [pp. 4-5].

Spillman, J. S., 1996c: American glass in the Bohemian style, The Magazine Antiques, Jan 1996, pp. 146-155.

Spillman, J. S., 2006: Splitting the rainbow: cut glass in color, The Gather, spring/summer 2006.

Taylor, G. L., 1991: COLORFUL CUTTING. Museum of American Glass, Wheaton Village, NJ. Exhibition catalog, 6 Apr - 27 Oct 1991, [6 pp.].

Waher, Bettye, 1984: THE HAWKES HUNTER. Privately printed, 151 pp.

Williams-Thomas, R. S., 1983: THE CRYSTAL YEARS. Stevens & Williams Ltd., West Midlands, England, 80 pp.

Woodward, W. H., 1978: ART, FEAT AND MYSTERY. The Story of Thomas Webb and Sons, Glassmakers. Mark + Moody, Ltd., England, 61 pp.

Jim Havens

Corning, NY

15 Feb 2007