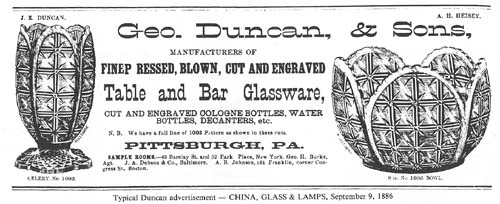

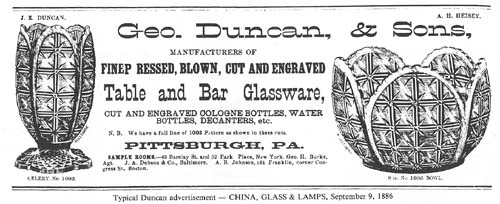

In 1950 Dorothy Daniel suggested that John Ernest Miller was associated with the Phoenix Glass Company of Monaca, PA, and that he patented at least one cut-glass pattern, pat. no. 16,997, for this company. While it is true that Miller patented a pattern -- he actually patented several -- all of his designs were intended for pressed glass, not cut glass as claimed by Howe in this article.. And, furthermore, there is no evidence that this long-time and highly regarded employee of the Geo. Duncan & Sons company of Pittsburgh was ever associated with the Phoenix Glass Company. Howe could have discovered all this by consulting Bredehoft et al (1987) and Innes (1976). In the former book there is the following quotation from the Pottery & Glassware Reporter of 2 Sep 1886 concerning pat. no. 16,997: "While [the pattern is] an imitation of cut glass, it is a good one ..." It was not called "Maltese Crosses" as stated by Howe. Daniel -- who is probably Howe's unnamed attributer -- called the pattern "Miller's Maltese Cross". The factory named it Maltese. The following illustration of examples of this pressed-glass pattern is reproduced from Bredehoft et al (1987, p. vi):

Howe claims that a second Miller design, pat. no. 17,186, was also intended for cut glass. Inspection of the patent's drawing (provided by Howe in his article) should have convinced him otherwise. The "cutting" that is shown between the handle of a pitcher and the pitcher's body is clearly an impossible task for any glass cutter. The Bredehoft et al and Innes references would also have provided the author with additional information about this pressed-glass "line", which is called "Zippered Block" by collectors, along with a few facts concerning Miller's life.

Howe claims that a second Miller design, pat. no. 17,186, was also intended for cut glass. Inspection of the patent's drawing (provided by Howe in his article) should have convinced him otherwise. The "cutting" that is shown between the handle of a pitcher and the pitcher's body is clearly an impossible task for any glass cutter. The Bredehoft et al and Innes references would also have provided the author with additional information about this pressed-glass "line", which is called "Zippered Block" by collectors, along with a few facts concerning Miller's life.

During the years covered by Howe's article Miller worked as foreman of the mold shop at Geo. Duncan & Sons, and he also held the position of superintendent (manager). At this company cutting appears to have been of fairly minor importance, limited to simple, non-patented patterns on colognes, decanters, and water bottles that were designed to sell for a low price. An example, shown on the right, has a "cut star" on a pressed-glass "Zippered Block" tumbler (Bredehoft et al, p. 96). Incidentally, the two Miller patents mentioned by Howe were not assigned by Miller to any company. While he could have sold one or the other to another company, including Phoenix, it is not reasonable to suppose that he did, given the fact that both patterns were produced (as pressed glass) by his employer, Geo. Duncan & Sons.

Finally, Howe raises the intriguing problem of Joseph B. Hill's design patent of 23 Oct 1888, no. 18,697. However, he merely repeats thirty-five year old information: that this pattern was assigned the name "Maltese Crosses" and attributed to the Phoenix Glass Company. Howe again coyly does not reveal the attributer's name, but we can readily discover it in Revi (1965, p. 258): it is Revi himself! Howe also fails to tell us that Hill retained his patent (he did not assign it to Phoenix), so the pattern could have been cut by any company Hill might choose, as pointed out by Revi. But because Hill's patent application (specification) was witnessed by Joseph Webb, who was an English etcher associated with Phoenix at this time (according to Pyne Press 1972), and because the company introduced a pattern called Webb in Mar 1888 (according to Howe), which is when Hill filed his patent application, one can easily connect the dots, although Howe chooses to ignor them. To conclude decisively that the Phoenix Glass Company cut Hill's patent is tempting but is not possible at the present time. See Hill's 1888 patent uncer the Phoenix Glass Company listing in the Shops 2 file in Part 2.

Incidentally, the late J. Stanley Brothers, Jr. wrote the following on his copy of the Hill patent: "Phoenix Glass Co. / (Positive)" (Archive).

N. B.: The Hill patent contains a major error that presumably was introduced by the patent's lawyer. Two sets of parallel miter cuts, shown on the patent's drawing, are not labeled (they are nos. 7 and 8) and, consequently, are not mentioned in the patent's specification. The Hill patent is one of only two rich-cut patterns found to date that result from eight intersecting sets of parallel miter cuts (see the motifs2.htm file in Part 1).

References:

Archive: The J. Stanley Brothers, Jr. files at the Rakow Library, Corning Museum of Glass

Bredehoft, N. M., G. A. Fogg, and F. C. Maloney, 1987: EARLY DUNCAN GLASSWARE. GEO. DUNCAN & SONS, PITTSBURGH, 1874-1892. Privately printed, vi + 176 pp.

Innes, Lowell, 1976: PITTSBURGH GLASS, 1797-1891. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 522 pp.

Pyne Press, 1972: PENNSYLVANIA GLASSWARE, 1870-1904. Princeton, NJ, 156 pp.

Revi, A. C., 1965: AMERICAN CUT AND ENGRAVED GLASS. New York, 497 pp.

Updated 1 Oct 2004