Early- and Middle-Period Cut Glass

Rare Cut Glass from the Portland Glass Company, 1863-1873

Articles concerning the Portland (ME) Glass Company, such as Clifton R. Sargent, Jr.'s that appeared in No. 152 of The Glass Club Bulletin (winter 1986/87, pp. 11-13), usually concentrate on the company's output of pressed glass, one of its main products. Little is heard of the company's cut-glass production even though the company began cutting glass early in its existence.

Articles concerning the Portland (ME) Glass Company, such as Clifton R. Sargent, Jr.'s that appeared in No. 152 of The Glass Club Bulletin (winter 1986/87, pp. 11-13), usually concentrate on the company's output of pressed glass, one of its main products. Little is heard of the company's cut-glass production even though the company began cutting glass early in its existence.

Sargent suggests that one of Portland's patterns, "Palmer Prism", can be considered to be the company's "rarest" pattern in pressed glass. Does it, therefore, follow that the cut-glass version of this pattern is even rarer? The writer does not know. In this article he presents an example of "Cut Palmer Prism" and lets the reader decide for himself. A brief summary of that remarkable family of glassmakers -- the Eggintons -- who played a significant role in the establishment of the Portland Glass Company and its early success is also included.

Before examining the example of "Palmer Prism" in cut glass, the careers of the Eggintons are briefly reviewed. Discussions of the Portland Glass Company seldom mention these glassmakers who, in addition, helped advance the development of the American cut-glass industry during its so-called middle and brilliant periods.

Thomas Egginton (1788-1850), the head of the family in England, was so highly regarded by the glass trade during the early nineteenth century that the British government hired him to train London workmen in glass making. And he was an accomplished violinist as well. He married three times: Thomas, from his first marriage, and Enoch and Oliver, from his second marriage, followed their father's vocation and were trained in the glass art in England prior to emigrating to the United States and Canada.

Enoch Egginton arrived in Canada in 1860 and soon found work at the Dorflinger Glass Company's new plant at Greenpoint, Brooklyn, NY. He was highly regarded as an all-around glassman and one who could not only supervise the building of a glass factory but could also direct the manufacture and decoration of its glassware. Accordingly, in 1863 he accepted an offer from Portland, ME to build a factory there for the recently formed Portland Glass Company and to supervise its operation.

Enoch arranged for the immigration of other members of his family to help him in Portland: his half-brother Thomas, and his wife, arrived in 1864, and his brother Oliver, his wife, and their four sons -- Joseph Augustus, Oliver Enoch (called "George"), Alfred James, and Walter Edward -- came over the following year. Both Oliver and Joseph were experienced glasscutters at this time while the younger men, George, Alfred, and Walter, were probably still cut-glass journeymen or apprentices. It is said that they all received their training in glass cutting in factories in the Stourbridge area of the English Midlands. Oliver himself was born in Birmingham in 1822 and undoubtedly obtained his early training there. Although usually listed as a glasscutter, he gained experience over the years in the other aspects of glassmaking, especially while working with Enoch in Portland. Later Oliver was to use this experience in Canada (note 1).

On 18 Sep 1867 the Portland Glass Company had a disasterous fire that resulted in a loss of at least $100,000 only half of which was covered by insurance. However, "the works was rebuilt and apparently by April 1868 operations were back to normal" (Wilson 1972, p. 321). Nevertheless, the company did not prosper as it had before the fire and in 1873 it went out of business, a casualty of the economic panic of that year.

At about the time of the fire, and probably as a result of it, Enoch, Thomas, and Oliver moved to Montreal, P.Q., Canada to manage a glassworks there, the St. Lawrence Glass Company. The company had been established earlier in 1867. Its products were highly diversified, but cutting seems to have been limited, initially, to glass shades (Stevens 1967a, p. 120; Stevens 1967b, pp. 45-7, 233). It is known that Oliver took his two younger sons with him to Montreal, but Joseph probably stayed in Portland to help re-establish Portland's cutting department after the fire. Enoch had started the company's cutting shop in 1864, but eventually it was managed by Joseph. Oliver's second oldest son, George, apparently remained in Portland with Joseph and his wife, the former Bridget Shannon of Portland, whom he married in 1869. The following year George "drowned while swimming in Lake Ontario on a visit to his parents in Montreal" (genealogy).

The years 1869 and 1870 brought additional misfortune to the Egginton family: Both Enoch and Alfred died during 1869 and the following year Thomas, in addition to George, also died. These unhappy events undoubtedly influenced Joseph to join his father, Oliver, in Montreal. This probably occurred in 1870 or 1871 when Joseph established a business there. A letterhead from his business describes Joseph as a "practical ornamental glass cutter". Oliver, in the meantime, assumed his brother's duties at the St. Lawrence glasshouse. A notebook, with batch formulae, that Enoch kept while in Montreal, and which also contains family notes by Oliver and Walter, was obtained by the Rakow Research Library, Corning, in 1993.

The St. Lawrence Glass Company operated for only a few years and closed, probably like the Portland company, as a result of the Panic of 1873, in 1875. By 1873 the company's future was likely in doubt. This must have been a factor in Oliver's decision to accept an offer that John Hoare made about this time for Oliver and his sons to work in Hoare's glass-cutting establishment in Corning. Hoare might have met Oliver in England where both men worked as glasscutters during the 1840s (Sinclaire and Spillman 1997, p. 123). As a result of Oliver's decision, he and his son Walter worked during the 1870s for the cutting shop that eventually became J. Hoare & Company. Joseph remained in Montreal. His business venture in was successful, but he too moved to Corning, probably about 1890.

When T. G. Hawkes, foreman at Hoare's shop, opened his own glass-cutting business in 1880 Oliver and Walter joined the new enterprise. Oliver eventually became supervisor of the Hawkes cutting shop, and Walter developed his talent for designing cut-glass patterns. In 1896 Oliver left Hawkes to found his own cutting shop, the O. F. Egginton Company. Walter accompanied him and eventually designed most, if not all, of the designs at his father's company. When Oliver died in 1900 Walter assumed the company's presidency, a position he held until the company was dissolved in 1918. Walter died in 1925. Joseph never worked for his father's company, but he did cut glass, sporadically, at T. G. Hawkes & Company. He also re-established the business he had in Montreal, which now included the designing of leaded ("stained") glass for windows and door panels. Joseph died in 1914 (note 2).

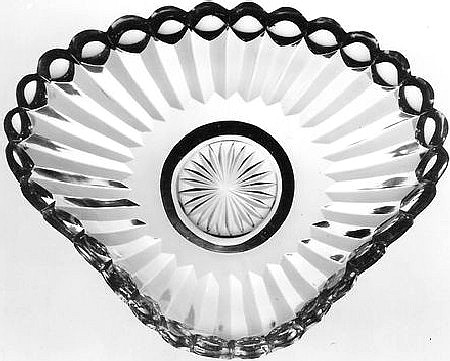

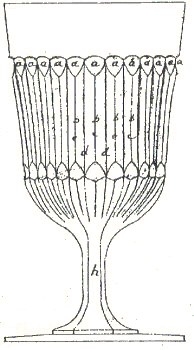

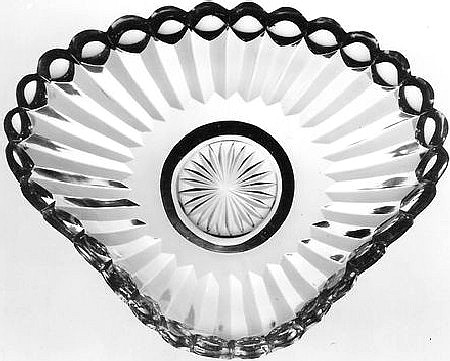

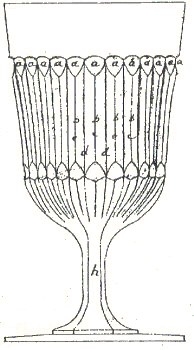

Sargent has pointed out that "no factory records, sales catalogues, or advertising material" exist for the Portland Glass Company. Consequently, it is necessary for today's collector to rely on U. S. patents for identification of patterns that can be attributed positively to Portland. The writer found the cut-glass dish that is the main subject of this article in 1983. Comparison of the dish's pattern with the patent, above right, for "Palmer Prism" removes any doubt concerning the dish's origin. Two views of it are shown here:

The dish has the following approximate measurements: L = 6", W = 5", H = 1.5", wt = 1 lb. It sold for $21 in 1996. The dish's overall shape mimics the shape of the pattern's indented scallops, which are described in the patent's specification as "three-corned figures". The profile view shows the dish's applied, wafer base on which is cut a 24-pt star.

According to Sargent, the pattern's patentee, Joshua Sears Palmer, "was manager and treasurer of the Portland Glass company from 1863 through 1869". He seems not to have been an experienced glasscutter. Perhaps Joseph Egginton helped him with his pattern. Its overall design, while simple, is quite sophisticated, and its "three-cornered figures" motif is unusual in cut glass.

The "Palmer Prism" patent's specification seems to have been written with cut glass in mind -- the word "cutting" is used -- but its use in pressed-glass is not precluded. Early design patents seldom specified the method of decoration to be used. This, understandably, has caused a degree of confusion in the history of American cut glass. Some patterns, such as the Portland company's other patented pattern, "Loop and Dart with Round Ornaments" (pat. no. 3,494), are obviously designed for pressed, not cut, glass. This also applies to the "Portland Tree of Life" pattern. While it, too, is said to have been patented, no patent has been found. Its attribution to the Portland Glass Company rests upon markings made in the mold. Additional pattern-names have been attributed to the company but, as Spillman has stated, "without illustrations they are of little help" (note 3, p. 17).

Sargent's article, together with the present one, confirm that "Palmer Prism" was produced in both pressed and cut glass. Just how "rare" each of these versions may be today is, however, an open question.

Acknowledgment: The writer greatly appreciates the considerable assistance he received at the Juliette K. and Leonard S. Rakow Research Library and from Jane Shadel Spillman and John Kohut, all of Corning, NY.

NOTES:

1. A genealogical report on the Egginton family, dated 12 August 1960 and prepared by George Edward Egginton, Oliver's grandson, has been of considerable help in reconstructing the family's early history. Also helpful have been five letters from Enoch Egginton in Portland to his brother William in England written between 1863 and 1865. All of this material is on file at the Rakow Research Library.

2. Obituaries consulted: Oliver F. Egginton (Corning Daily Journal, 19 Mar 1900), Joseph A. Egginton (Corning Evening Leader, 29 Jan 1917), and Walter E. Egginton (The Evening Leader, 12 Mar 1925).

3. Jane S. Spillman, "A 19th Century Notebook in the Gillinder Archives", The Glass Club Bulletin, No. 194, autumn 2002, pp. 9-20.

Updated 20 Oct 2005

Articles concerning the Portland (ME) Glass Company, such as Clifton R. Sargent, Jr.'s that appeared in No. 152 of The Glass Club Bulletin (winter 1986/87, pp. 11-13), usually concentrate on the company's output of pressed glass, one of its main products. Little is heard of the company's cut-glass production even though the company began cutting glass early in its existence.

Articles concerning the Portland (ME) Glass Company, such as Clifton R. Sargent, Jr.'s that appeared in No. 152 of The Glass Club Bulletin (winter 1986/87, pp. 11-13), usually concentrate on the company's output of pressed glass, one of its main products. Little is heard of the company's cut-glass production even though the company began cutting glass early in its existence.