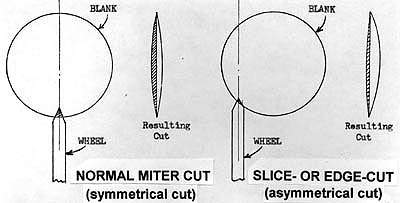

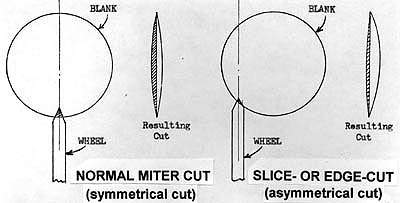

Comparison-sketch of miter and edge or slice cutting, showing the resulting asymmetrical cut produced by the latter technique (after Elville 1960, p. 179).

Few motifs in this group have been named, and only a scattering

of descriptive terms such as "large, shallow diamonds" and the

"eye-lid" motifs appear in the literature. Interestingly the

large, shallow diamonds required twice the number of passes

over the cutting wheel as did the smaller "relief" diamonds

cut later with the glass blank held perpendicular to the miter

wheel. As a result pieces cut in this old style are easily

identified.

To test whether a large, shallow diamond has been cut using edge

or slice cutting run your finger-nail across the "split"

that defines the diamond. Your finger-nail will catch on a

"step" that results from the fact that the two sides of the cut

were made independently. It is impossible to cut adjoining cuts

to absolutely identical depths, and, as a result, a tiny step is formed.

Thorpe (1935, p. 215) argues persuasively that the large, shallow diamond (a.k.a. "the broad relief style") is a mirror-grinder's motif -- "a bevel-edged mirror reduced to the nth [degree]" -- introduced by the English grinder Thomas Betts in the middle of the eighteenth century. Thorpe thus regarded this motif as an English, rather than a German, invention. In the example illustrated here a later date is suggested in light of the accompanying star-cut base. This latter figure is placed on a cut, circular boss, and its rays show the tiny step that indicates that each ray was double slice cut.

Plate or tray. Colorless, lead glass. Completely cut except at the rim (possibly left uncut to accept a silver mounting). Band of slice-cut large, shallow diamonds bordered with flutes. Early miter-cut 24-pt star base. English, late eighteenth century. Sold for $50 in 2007. D = 8.75" (22.2 cm), H = 1.25" (3.2 cm), wt = 1.25 lb (0.5 kg).

Apparently, during the nineteenth century the miter wheel, with an apex

angle much greater than 90 degrees, was sometimes used to cut

large, shallow diamonds in imitation of the earlier style. No

step can be felt on these pieces. This supposition is supported

by observations that the blanks used often had poor color,

probably an attempt to imitate the color of the glass of the

previous century. Ironically, authentic eighteenth century lead glass

is often of very good quality. Fake cut glass is not exclusively

a twentieth century phenomenon!

Before the two-piece butter dish became commonplace on Victorian

tables three-piece "butter coolers" were popular. Butter itself

was considered an appropriate accompaniment to the wine that was

served after dessert. The Frenchman Francois de la Rochefoucauld,

described dining at a well-to-do English home in 1784 where,

after the main courses, which took "four or five hours", the

table-cloth was removed and the table prepared for some serious

drinking: "On the middle of the table is a small quantity of

fruit, a few biscuits (to stimulate thirst) and some butter, for

many English people take it at dessert." (as quoted in Warren

1981, pp. 246-7) The butter would have been stored in a cool

place in wooden, or perhaps ceramic, tubs. But when brought

to the table, gleaming under candlelight, it would have been

transferred to a butter cooler, most likely elegantly cut in the

situation described above but unadorned when used in more modest

circumstances.

It is unusual to find all three components of a butter cooler

intact today: bowl, cover, and underplate, the latter providing

ease in carrying the cooler. Some underplates had a saucer-shaped

profile, suggesting an area for ice or cold water, but other

underplates do not have such a profile. Because it is likely that

the cut glass butter cooler was used only for temporary storage

its contents would not require icing. But the butter probably

became quite soft during the postprandial drinking that could

easily take up to "two or three hours". (The ladies would have

"withdrawn" after taking a glass or two of wine, but they would

likely have enjoyed a glass of ratafia or some other cordial in

their "withdrawing" room while the gentlemen remained ensconced

in the dining room.)

Several years ago the writer visited a consignment shop in

Barrington, RI and witnessed the clerk about to exhibit a three-

piece cut glass butter cooler. Wasting no time he quickly inspected

the item and found it little damaged and displaying, in

abundance, that type of cutting we have identified as edge- or

slice-cut. The price tag that read "three pieces of glass,

$12" did nothing to discourage an immediate purchase. But a

major mystery presented itself: Could such an item have

survived from the days of de la Rochefoucauld? If so, who made

it? Or could it be a more recent "reproduction"?

The butter cooler from the consignment shop. Colorless, lead glass. Slice cutting showing the "eye-lid" motif. Probably Continental, date uncertain. H= 7.25" (18.4 cm), D = 7" (17.8 cm), wt = 2.75 lb (1.5 kg). Minor chips. Sold for $100 in 1991.

Some of these questions were eventually answered, but only after

several years spent in intermittent investigation. The major

source of information was provided by the research of

M. S. Dudley Westropp who was associated with the National

Museum of Ireland for many years. He will be discussed in the Anglo-Irish glass

file for his contributions to the study of Irish glass. Here

we refer only to his comments concerning a bowl that has a shape

similar to the butter cooler's and that has an identical

edge-cut

pattern that includes the "eye-lid" motif. Westropp was writing

just prior to 1920 when his book was first published. (The 1978

edition, used here, includes his later notes, together with the results of

independent research on Irish glass by the book's editor, Mary

Boydell.) Westropp's comments, which follow, are pertinent:

I would like to call attention to the cut-glass bowls often of a very slightly greenish metal, with solid truncated cone-shaped base, and usually having rather shallow geometric cutting.These are very often said to be of Irish manufacture and especially of Waterford, but on what grounds I have never been able to ascertain. As far as my experience goes I have never found them among any old glass that has any pretentions to be Irish, and I do not consider them to have been made in Ireland at all. The older ones are probably English, but the modern fakes, of which a goodly number are passed off as Waterford, are generally continental. (Westropp 1978, p. 195; also see Plate XXXV, p. 160)

A few years ago an advertisement was spotted in The Magazine

Antiques that showed a butter cooler remarkably similar to

the one found at the consignment shop. Eventually its owner, a

general-line antiques dealer in London sent the writer a

brochure that clearly shows a twin

to the writer's butter cooler. Unfortunately more than 70 years

after Westropp's discussion she was unable to provide any

additional information beyond mentioning that such butter

coolers usually are considered to be Continental, dating from

the first half of the nineteenth century. (The term seems to have

been in use as late as the mid-nineteenth century.) A partial answer

to the "mystery" of the butter cooler is that those we

find today are likely to be of Continental origin

and date from the early nineteenth century rather than having

been made in Ireland in the eighteenth century. The example from the

consignment shop was made of lead glass and had a fairly dark hue

to its glass-metal: not greenish but gray. The entire surface

was cut with excellent accuracy as can be seen in the foregoing image. The cutting exhibits the characteristic "step" of early edge-cut glass. While this style prevailed during the years preceding the miter-cut style, there is no reason why it should have been limited exclusively to those early, pre-1800 years. It is often remarked that cutting styles tend to "linger". As the English glassman, H. J. Powell, put it:

There is a common belief that certain styles of cutting indicate certain dates. It is true that a certain style may indicate that a glass was not made before a certain date, but a style, once introduced, was constantly copied, and the copying is still continued (Powell 1923).

Indeed, "the copying is still continued", is well-illustrated by this vase cut by T. G. Hawkes & Company, probably during the 1920s (Sinclaire and Spillman 1997, p. 102). The blank is number 3223. It is solid blue and has a height of 8.6" (21.8 cm). The "eye-lid" motif is featured (Image: Internet).

Updated 15 Jul 2007