American Cut Glass Association (ACGA) - Jim Havens' "Guide to American Brilliant Cut Glass"

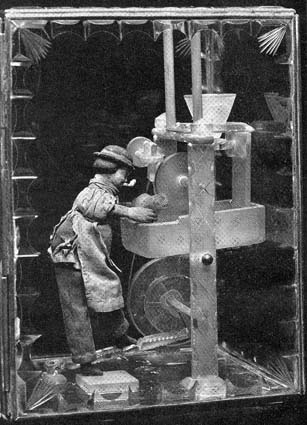

In the early history of cut glass all four stages necessary to produce a cut-glass article -- marking, roughing, smoothing, and polishing -- were carried out by the same individual, such as the Irish glass cutter shown at the left. This "rare working model" is taken from the frontispiece in Davis (1964). No additional information is given, and the present location of the model is not known. Note the foot-treadle.

In the early history of cut glass all four stages necessary to produce a cut-glass article -- marking, roughing, smoothing, and polishing -- were carried out by the same individual, such as the Irish glass cutter shown at the left. This "rare working model" is taken from the frontispiece in Davis (1964). No additional information is given, and the present location of the model is not known. Note the foot-treadle.

As specialization developed among the workmen during the nineteenth century, an object being cut would have been passed along, "assembly-line" fashion, from marker to rougher to smoother to polisher, especially in the larger cutting shops. But it was still possible to find well-trained individuals who could take an unmarked blank and produce a finished product. This is also true today.

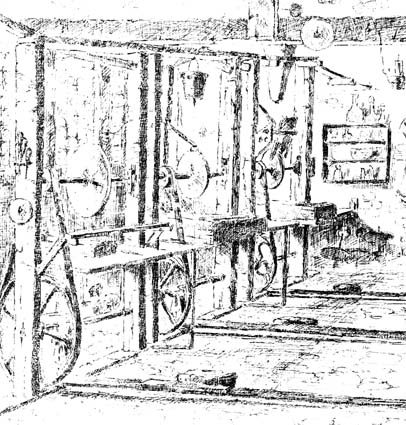

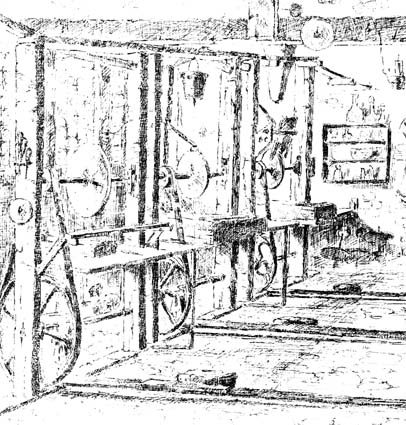

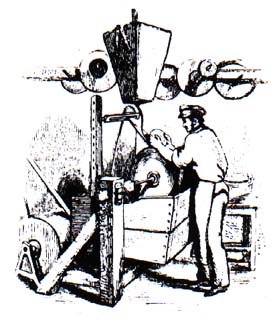

One can imagine the following "Interior of a primitive hand glass-cutter's shed" (Plate II in Stannus 1921) as a kind of proto-assembly line with frames designed specifically for cutting, smoothing, and polishing, although in this case probably only one individual operated the three frames, all of which are powered by foot-treadles.

The frame on the right, with its overhead hopper containing a mixture of grit and water, is equipped for roughing. Note the shield over the iron wheel to protect the rougher. The middle frame is intended for smoothing on a stone wheel, the conical hopper having been replaced with a bucket of water. The frame on the left is possibly intended for polishing. For this purpose a pan of pumice and water would have been placed under the hardwood wheel, and the mixture "fed up" to the wheel by the workman. Cutting in this shed would have been limited to shallow motifs such as flutes and bullseyes together with slice-cutting. Deeper, prismatic cutting at this time would have been limited to larger operations where steam power was available.

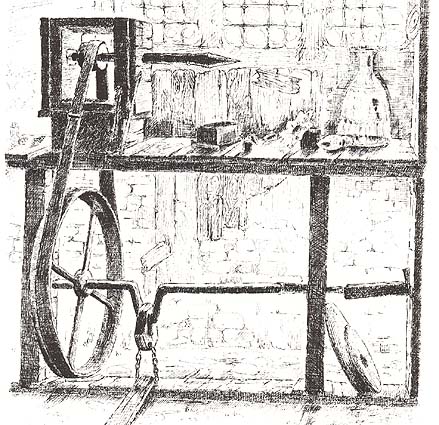

The following drawing shows a more specialized piece of equipment at the "primitive hand glass-cutter's shed": a "Device for stoppering bottles and opening pans" (Plate III in Stannus 1921). The foot-power illustrated in the previous drawing is more clearly seen here. These drawings represent a small-time operation in Ireland (and elsewhere) during the first half of the nineteenth century.

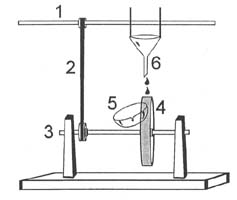

The diagram at the right schematically illustrates a typical cutting frame, such as those used in the previous Irish examples. Here, however, the "foot power" has been replaced with a drive shaft powered by steam, which was available in England by the turn of the nineteenth century and in the United States soon thereafter. By the 1830s the Irish glasshouse at Waterford was complaining about the large volume of cut glass its cutting shop was turning out because of the use of a steam engine.

The diagram at the right schematically illustrates a typical cutting frame, such as those used in the previous Irish examples. Here, however, the "foot power" has been replaced with a drive shaft powered by steam, which was available in England by the turn of the nineteenth century and in the United States soon thereafter. By the 1830s the Irish glasshouse at Waterford was complaining about the large volume of cut glass its cutting shop was turning out because of the use of a steam engine.

(1) is a drive shaft powered by a steam engine (not shown); (2) indicates belt and pulleys that transfer power to the (3) shaft with its (4) cutting wheel. (5) is the object being cut, in this case a bowl that is being smoothed on a sandstone wheel which is being kept moist by water dripping from a (6) funnel. This diagram, together with the following sketches, somewhat modified, are taken from "Avoiding new cut glass", Antique & Collectors Reproduction News, Vol. 6, No. 2, p. 14 (Feb 1997).

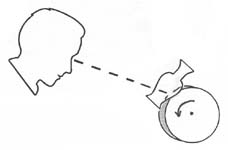

The following sketches illustrate the two techniques of overhand and underhand cutting. On the left a vase is being cut by the overhand, or normal, method. At some point, however, the contact between the vase and the wheel will become invisible to the cutter, especially if the cutting is a "rich" one. To finish his work the cutter must shift the vase to a position beneath the wheel and commence underhand cutting, a specialization that developed during the eighteenth century. Now the wheel itself obstructs the cutter's view. Consequently, he must remove the vase from the wheel periodically to check the progress of his "blind" cutting which is assisted by the actual sound of the cutting process. Experience obviously plays a major role in successful underhand cutting. It can be important today. A collector who is seeking "restoration" may find that the task is impossible unless the craftsman is adept at underhand cutting. Not all cutters have this ability. Fortunately, however, most repairs can be carried out using the normal techique of overhand cutting.

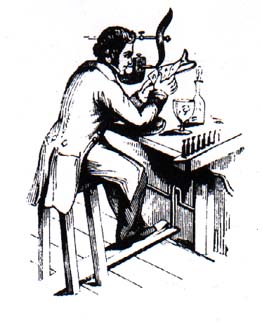

The following drawings illustrate a glass cutter on the left and a glass engraver on the right. Although the engraver in period illustrations is invariably shown sitting at his lathe, the glass cutter may be either standing, as here, or sitting (from Pellatt 1849).

Updated 17 Apr 2003