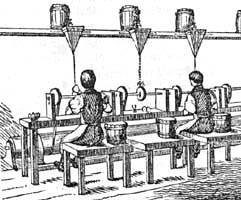

In some principal establishments, steam power is used for giving motion to a shaft which cases the revolution of numerous large wheels or drums fixed thereon, and each of these being connected by a band with a pulley on the axle of a smaller wheel, occasions the latter to revolve with great celerity: these small wheels are the cutting instruments. . . .

In some principal establishments, steam power is used for giving motion to a shaft which cases the revolution of numerous large wheels or drums fixed thereon, and each of these being connected by a band with a pulley on the axle of a smaller wheel, occasions the latter to revolve with great celerity: these small wheels are the cutting instruments. . . .

The small wheels are so arranged, that each can be unfixed without difficulty, and another substituted of a form better suited to the work in hand, or of a material more adapted to the stage of the process.

As regards their forms, these cutting wheels are either narrow or broad -- flat-edged -- mitre-edged, that is, with two faces forming a sharp angle at their point of meeting -- convex -- or concave. In fact, so various are the wants of the workman, that as many as forty or fifty wheels having differently shaped edges, are to be found in the workshop.

The materials employed in the formation of these cutting implements are, iron, both cast and wrought, Yorkshire stone, and willow wood. Wrought iron is, indeed, only used for cutters of the narrowest dimensions, and which it would therefore not be possible to make sufficiently tough of cast metal. Iron wheels are used only for the first or toughest part of the operation, and their employment is even dispensed with altogether, where it is intended that the pattern shall be at all minute; as the metal and the sand, which must be used in conjunction with it, would act too roughly, and frequently chip away portions of the glass. For such minute works, and for smoothing down the asperities which will always be occasioned where iron cutters have been applied, a wheel of Yorkshire stone, moistened with water, must be used. The further smoothing and subsequent polishing of the cut surfaces are effected with wooden wheels; for the first of these objects, the edge is dressed with either pumice stone or rotten stone; and for imparting the high degree of polish that is requisite for properly finishing the process, putty-powder is employed.

Beneath each one of the cutting wheels, a small cistern is fixed to receive the sand, water, or powder which has been used; and over the wheel, a small keg or conical vessel is placed, the cock or opening at the bottom of which is so situated and regulated, as that the requisite quantity of moisture will be imparted from it to the wheel. The vessel which is placed over the iron wheel is furnished with fine sand, and into this water is admitted in such quantity as will ensure the constant delivery of the moistened sand upon the face of the wheel in such proportion as the workman finds most desirable. The emery powder, rotten-stone, or putty powwder, are applied from time to time as required by the workman, on the edge of the smoothing or polishing wheel.

. . . Placed at his right hand each workman has a small tub containing water, wherewith from time to time he washes away the particles of sand or powder which may adhere to the glass, that he may the better judge as to the progress of his work.