American Brilliant Cut Glass, 1876-1917

by John C. Roesel

3,500 Years of Glass

Glass, that remarkable substance born of sand, alkali and fire, has fascinated and served humankind for more than 3,500 years - ever since some long-forgotten Middle Eastern artisan stumbled upon a way to control its manufacture. From quite beautiful luxury items prized by the pharaohs, glass has evolved into highly sophisticated functional uses deeply imbedded in the fabric of our twentieth century civilization. One doesn't have to look beyond the confines of his own household to realize the vast variety of ways that glass serves everyday needs.

Glass used decoratively can take many forms. It can be made opaque or transparent, clear or colored, brittle or soft, durable or fragile. It can be molded or blown, cut, engraved, enameled or painted. In the hands of an artist, it becomes a medium that permits an almost limitless variety of techniques in the quest for a finished object of great beauty.

"Cut Glass" Defined

Let's single out only one decorative technique, explore its demands and scope, and perhaps learn to admire and appreciate the end product. Let's limit our attention to "cut glass", which must be carefully defined. "Cut glass" is glass that has been decorated entirely by hand by use of rotating wheels. Cuts are made in an otherwise completely smooth surface of the glass by artisans holding and moving the piece against various sized metal or stone wheels, to produce a predetermined pleasing pattern. Cutting may be combined with other decorative techniques, but "cut glass" usually refers to a glass object that has been decorated entirely by cutting.

Cut glass can be traced to 1,500 B.C in Egypt, where vessels of varying sizes were decorated by cuts made by what is believed to have been metal drills. Artifacts dating to the sixth century B.C. indicate that the Romans, Assyrians and Babylonians all had mastered the art of decoration by cutting. Ever so slowly glass cutting moved to Constantinople, thence to Venice, and by the end of the sixteenth century, to Prague. Apparently the art did not spread to the British Isles until the early part of the eighteenth century.

Early Cut Glass in America

Although glass making was the first industry to be established in America at Jamestown, Virginia in 1608, no glass is known to have been cut in the New World until at least 160 years later. Henry William Stiegel, an immigrant from Cologne, Germany, founded the American Flint Glass Manufactory in Manheim, Pennsylvania, and it was there in about 1771 that the first cut glass was produced in America.

For the next sixty years the "Early Period" of American cut glass, our wares were virtually indistinguishable from English, Irish and continental patterns, and little wonder, for most of the cutters originally came to this new country from Europe. About 1830 which historians label the beginning of the "Middle Period" American ingenuity and originality began to influence the industry, and a national style began to develop. This came into full flower about the time our country was preparing to celebrate her hundredth birthday and what is now termed the "Brilliant Period" began. From about 1876 until the advent of World War 1, American cut glass craftsmen excelled all others worldwide, and produced examples of the cut glass art that may never again be equaled.

Forces of Change

Several exciting events dramatically improved American's cut glass industry, and brought about a superiority that won world acclaim. Near the beginning of the Brilliant Period, deposits of high grade silica were discovered in this country, leading to glass-making formulas vastly better than those used in Europe. Almost simultaneously, natural gas replaced coal-fired furnaces, with resultant better controls of the glass-making process and electricity brought about replacement of clumsy steam-driven cutting wheels.

At the same time, many of Europe's finest glass makers and cutters were immigrating to this country to seek their fortunes, and they found ready markets for their talents when America moved into a very prosperous era in the closing quarter of the 19th century. Cut glass became a symbol of elegance and leisure, and demand for beautiful glass products spurred intense competition and creativity within the industry.

Brilliant Period Events

High labor cost inherent in the manufacture of cut glass has always made it a luxury item. Unfortunately, until late in the nineteenth century, American glass houses found it difficult to compete against a vogue that held European glass to be superior to the domestic product. The prejudice began to disappear when eight enterprising American companies showed their beautiful wares at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Rail transportation brought record attendance to our nation's hundredth 'birthday party', and throngs were captivated by elegant cut glass tableware, lamps, perfume bottles and other fine products on display. A boom was sparked that lighted the might glass furnaces throughout the northeast, and the Brilliant Period had indeed begun.

Stunning new patterns quite unlike earlier European designs were developed and patented. Patterns were given intriguing names, and leading glass houses began advertising campaigns urging collection of whole sets of goblets, tumblers, wine glasses and finger bowls in the new designs. Cutting shops proliferated to meet the demand for fine pieces of cut glass being sought by wealthy American households.

The blossoming industry received another boost at the 1889 Paris Exposition when grand prizes were awarded to the T. G. Hawkes Company of Corning, New York for two patterns named Grecian and Chrysanthemum. Worldwide acclaim immediately followed, breaking for good the specter of European superiority. Incidentally, in 1903, Thomas G. Hawkes teamed with an Englishman, Frederick Carder, to found the Steuben Company; to this day the world's most famous glass house.

Just four years later at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, The Libbey Glass Company of Toledo garnered the top awards for cut glass with their Columbia and Isabella patterns. Again popularity increased and huge sets of American cut glass tableware were ordered by the White House, by the presidents of Mexico and Cuba, by Edward VII of Great Britain, and by many industrial tycoons of the day. American cut glass had reached the zenith in its acceptance throughout the world. It had no peers.

Decline of American Glass Industry

Since true cut glass is entirely hand-decorated, high labor costs made it extremely expensive and out of reach to all but the affluent class. Intense competition, both domestic and from abroad, and the introduction of inexpensive pressed glass in patterns imitating cut glass, forced cost cutting short cuts on the dynamic, new American industry. These, about 1897, molding processes and acid polishing techniques began to be used, and inferior products crept into the market. The vogue of setting entire tables with glass was passing, and the industry began its decline. During the Brilliant Period nearly 1,000 glass cutting shops were established, by 1908 less than 100 remained. A number of leading companies continued to maintain their high standards throughout the waning years, and thereby attracted the finest designers and most skilled craftsmen, who from 1908 to 1915 produced some of the most elegant patterns of cut glass ever created. One author has aptly referred to this as the "Era of Super Glass."

The outbreak of World War I dealt the final blow to the fascinatingly brief birth, growth and decline of a uniquely American achievement. Brilliant cut glass. Lead oxide - an essential ingredient in glass made for cutting was needed for more urgent uses, and by the time the war ended, the few factories that had managed to survive used their resources to produce less costly glass. Thus ended an era of Yankee ingenuity, never to return.

Understanding Cut Glass

To appreciate fully the magnificent craftsmanship that resulted in America's exquisite cut glass, one must have a basic understanding of the nature of the glass itself, as well as the processes for forming and cutting individual pieces.

Volcanoes make crude glass constantly, called obsidian, but fine glass requires purity of ingredients, blended under ideal conditions, by talented and experienced master glassmakers. All glass that is to be decorated by cutting requires the addition of up to 40% lead oxide, a chemical that makes ordinary glass soft enough to cut against moving wheels without shattering. Leaded glass is called "crystal". All crystal is a type of glass, but all glass certainly is not properly called crystal.

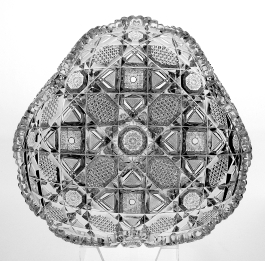

Cut leaded crystal (or cut glass) has three distinguishing characteristics: a bell-like ring when gently tapped with the finger, a clarity and brilliance unmatched by pressed or molded imitations, and weight noticeably greater than the same sized piece made of unleaded glass. America's Brilliant cut glass is appropriately named, for that is literally what it is. The cutting is brilliant because it is sharp and deep, reflecting light from highly polished surfaces. It is deep because it was made from leaded crystal that was beautiful in its clarity even though thick enough to be cut in high relief. Imaginative designers improved upon traditional motifs, arranging them in varying ways to provide for optimum reflective surfaces. American Brilliant Period cut glass was the end product of talented, resourceful craftsmen who capitalized on new glass technology, using new cutting methods made possible with electric powered cutting tools - all at a time when beautiful handmade articles were more appreciated than their machine made counterparts.

Unlike potters, weavers, basket makers or furniture craftsmen, who usually design and make their art objects while working alone, cut glass is the end product of a number of people, all of whom must work to the highest standards of perfection to create an object of exquisite beauty. Let's briefly trace the steps in the manufacturing process of cut glass, to understand the difficulty that must have prevailed in maintaining peak levels of quality from start to finish. Let's explore the skills that made this such a unique art form.

Making Leaded Crystal for Cut Glass

First, the formula consisting of silica, potash, lead oxide (and perhaps other ingredients) was melted in a 'monkey pot', or furnace, until the temperature reached 2400 degrees Fahrenheit, at which time the red hot, molten glass (called "metal") was ready to be worked. Four workmen were required to work each glass pot. The first, called the "gatherer", collected a ball of molten glass (called the "gather") on the end of his blowpipe, a hollow tube about four feed long. He blew air into it, let it cool a few hundred degrees, and then rolled it on a metal slab called the 'marver" to permit the glass to consolidate. Nest, the "gaffer", who was seated in an armchair, blew the "gather" into the desired shape. His assistant, the "servitor", reheated the glass when it cooled too much, and helped the gaffer add stems, feet, handles, or other parts to the piece, as required to finish it.

The fourth member of the team, an apprentice called the "carry in boy", lifted the finished item with pinchers and carried it to the "lehr", or annealing oven, where the piece was gradually cooled to room temperature. It could take as long as nine days in the lehr for cooling to occur without risk of the piece shattering before being ready for cutting. Once cooled, the "metal" or "blank" was simply a smooth, shaped piece of leaded crystal, without decoration of any kind, that was now ready for the next team of craftsmen.

The Process of Cutting Glass

When the blank was brought from storage for cutting, it was first marked by a designer with outlines of the decoration. Cutting was begun by the "rougher", who held the blank against a rapidly moving, beveled, metal wheel, kept constantly moistened and cooled by a fine stream of wet sand dripping from an overhanging funnel. He followed the designer's marks, making incisions by pushing the glass down against the wheel. He was blind to the contact of the wheel with the glass, except for what he could see through the glass - looking from inside to outside. He learned to judge the dept of the cut simply by the sound of the wheel and the "feel" of the piece in his hand. Various sized wheels were used to make the many different sized cuts required to complete the design.

Next, the piece went to the "smoother", who went back over all the rough cuts with stone wheels called "craighleiths." Thesmoother also initially cut some of the small lines on the motifs, as indicated by the design. Finally, the "polisher" finished the piece by polishing each cut with wooden wheels made from willow, cherry or other softwoods. Rottenstone or pumice was used with the polishing wheels to give a lustrous appearance to the cut, leaving no imperfections on the gleaming surfaces.

Early in the Brilliant Period one cutter did all cutting on a single piece. Since changing wheels to accommodate various sizes and depths of cuts could occupy sixty percent of a cutter's time, American assembly line methods were quickly adapted by the glass cutting industry. Each cutter was given a different sized wheel, and by passing a piece from station to station, productivity was immensely increased. Imagine, if you can, the true craftsmanship required from every member of the manufacturing and cutting teams, for cut glass of magnificent quality and unsurpassed beauty to have emerged, and to have become the unchallenged best in the history of the art form.

Cut Glass Today

Leaded glass is being cut today in Ireland, France, Belgium, West Germany, eastern European countries, Korea, Mexico and elsewhere, but careful comparison will show that the very best and most expensive does not rival the quality, craftsmanship and intrinsic beauty of most old American cut glass. Skillfully used advertising has romanticized much modern day cut glass to acceptance by the American public much beyond its true value, if compared with similar items still available from the American Brilliant Period.

If you are intrigued by the shimmer and sparkle of faceted glass, you are probably very familiar with such household names as Baccarat, Cristal d'Arques, Lalique, Orrefors, St. Louis, Val St. Lambert, and the ever-popular Waterford. Do you likewise recognize and know something about these equally famous names: Dorflinger, Egginton, Hawkes, Hoare, Jewel, Libbey, Meriden, Sinclaire, and Tuthill? All of the former are foreign, all of the latter are American - Brilliant Period American.

Collecting Brilliant Period Cut Glass

If you now know little or nothing about Brilliant Period cut glass, you have an exciting adventure awaiting you, for minimum effort will acquaint you with a thoroughly American art form that is rapidly being rediscovered and appreciated by connoisseurs and collectors across the land.

In some respects there is much to learn, for thousands of patterns were cut by hundreds of shops, and only a small percentage has been confidently identified. Some have maker's signatures, others have only wear marks. Some glass was wood-polished, some acid-polished, and it helps to know the difference. Hobstars and fans, strawberry diamonds and flutes, beading and chair caning, are but a few of the motifs that make up American designs, and all need recognition. Some superb, some fine and some inferior glass was cut, and it is mandatory that quality be judged before a purchase is made.>

On the other hand, collecting American Brilliant Period glass is one of the simplest hobbies you can undertake. The subject is only cut glass produced by only one nation. Its manufacture spanned less than half a century. Most of the best was made by the nine leading glass houses previously named. Contrast that to the extensive study necessary should you opt to collect paintings, porcelains or pottery, and knew nothing about any of the three fields. The choice should be clear, if glass excites you.

American Cut Glass Association

The non-profit American Cut Glass Association, founded in 1978, has grown rapidly to more than 1,700 dedicated enthusiasts, who have reproduced long forgotten cut glass catalogs to aid identification of manufacturers and patterns. An informative publication, The Hobstar is mailed regularly to the membership. A summer convention brings together experts for demonstrations and seminars, to widen knowledge about the fascinating hobby of collecting. Leading dealers participate in convention activities, and bring choice pieces for sale. A major feature of each convention is a member's only collector's sale night, where many fine items change hands and add to growing collections.

Regional chapters of the national association have been formed, to bring study of the hobby closer to a growing list of participants. Meetings are held throughout the year, with "show and tell" sessions and visits to inspect other member's collections.

Brilliant Period cut glass, forgotten for about sixty years, has been rediscovered, and is being collected and preserved for future generations to appreciate and enjoy.

Tips for New Collectors

If you would like to join the host of budding collectors, consider these suggestions:

1. Borrow or purchase one or more authoritative publications about Brilliant Period glass, to start the learning process.

2. Join the American Cut Glass Association (and a local chapter, if one is nearby) to learn from others who have accumulated some knowledge about the art form.

3. Obtain a reference from an Association member to one or more reputable, knowledgeable dealers in your area, from whom you can both learn and buy with confidence.

4. Attend as many auctions, antique shows and "estate" sales as possible, to see, feel, and ask questions about American cut glass. Be prudent about making purchases until you achieve a reasonable level of knowledge.

5. Take the "plunge" and buy a piece of glass to start your own collection. You may make an occasional mistake, but with the foregoing preparation, it should not be a too costly one.

If you already have American made cut glass that belonged to a grandmother or another family member, cherish it as you would any prized possession, for no more like it will ever be made. If you are looking for a rewarding hobby, consider becoming a collector. Fellow collectors are a friendly clan, eager to help the newcomer.

Whatever you do, take joyful pride in those years, the years of the Brilliant Period, truly a part of our great American heritage.