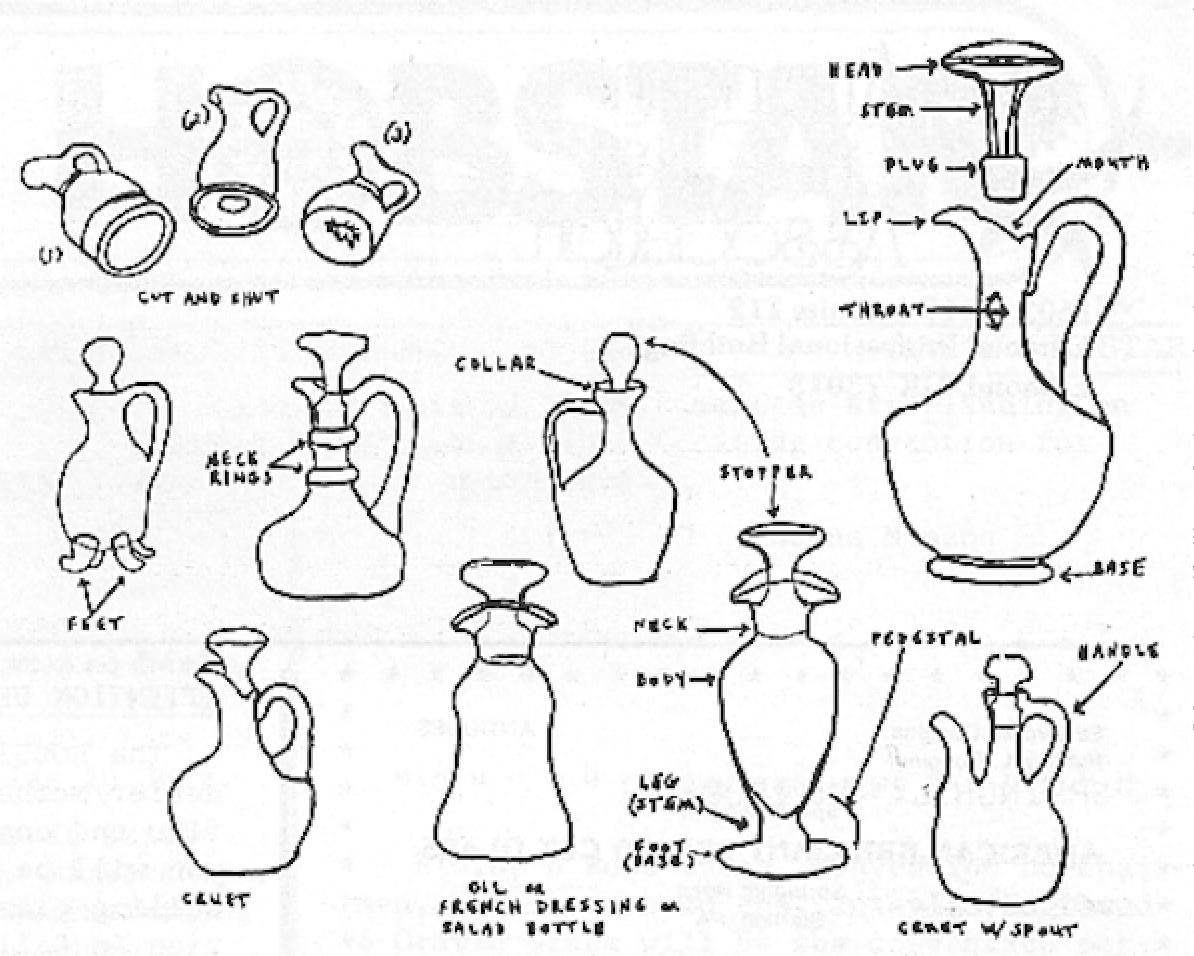

Cruets

By Patte and Peter Tomlinson

Reprinted from The Hobstar, March 1986

CRUET or CRUET BOTTLE is derived from the Dutch "Kruicke." It was sometimes spelled "crewet." A cruet is a small jug—shaped receptacle, usually with a lip or spout, a handle, and a stopper or lid, used for serving liquid condiments (oil, vinegar, also lemon juice, garlic juice, etc.) at the table or to hold wine or water at altar service. When made to be set by itself on the table, the cruet was a flat—bottomed small jug with a narrow neck, similar in shape to the carafe, but differing in that the cruet had a stopper and usually an applied handle. Cruets were free—blown, blown—in—the mold, and often decorated with etching, cutting or enameling; many later examples were of pattern glass. CASTER BOTTLES were cruets made to be set in stands or frames, did not have handles, and were much narrower overall.

The early form of mallet—shaped cruet bottle persisted up to the middle of the 18th century. Later, the shape changed to pyriform-that is, pear-shaped-and still later this shape was provided with a pedestal foot.

During the last quarter of the 18th century, two new styles appeared: a cylindrical bottle with a tapering neck (1776) and, in response to the classical influence, an urn-shaped bottle mounted on a spreading foot (1778). These styles persisted up to the end of the century.

A cruet with a pierced cover used for dry ingredients such as salt, pepper, dry mustard, sugar, etc. is called a CASTER or CASTOR. Some have a neck with interior threading for se-curing a threaded stopper or external threading for a screw cap. A SIFTER or SHAKER is also a caster or castor. Any bottle with a sprinkler top may also be called a CASTING BOTTLE.

Many different styles were followed ranging from a simple cylindrical shape to elaborately gadrooned, fluted, or globular bodies. The fretted lids were invariably decorated with intricately pierced patterns. Casters may be found individually, though sets of three in varying sizes were fashionable in the 18th century.

In American silver, the silver-plated revolving caster was a table ornament in general use in the second half of the 19th century. The rotary caster was patented in 1862. These condiment holders generally consisted of six bottles set in a base with either a pedestal or four feet, with an elaborate handle in the center. The bottles were of cut or pressed glass.

A MUFFINEER is derived from the use of sprinkling salt on buttered muffins. Muffineers are similar in form to casters but are somewhat smaller in size and with finer perforations. As a rule, muffineers are usually made in sets of three; one being considerably larger than the other two. The smaller two were used for Jamaica and cayenne pepper, while the large one was used for sugar.

VARIATIONS OF CRUETS

Oil and vinegar bottles fused together with spouts or necks pointing in opposite directions to provide pouring from either without spilling from the other are DOUBLE CRUETS or DOUBLE BOTTLES or DOUBLE FLASKS.

A double cruet may also be called a GEMEL. The term was derived from the Zodiac sign of Gemini-The Twins. Gemels were very popular in the U.S. during the first half of the 19th century.

A bottle that is divided internally into three or more compartments, each with its own mouth or spout is a TRIPLE BOTTLE or MULTIPLE BOTTLE.

CRUET/CONDIMENT SETS

CONDIMENT SETS are a matched group of containers usually with a tray or rack, including containers for pepper, salt, and mustard, stoppered cruets for oil and vinegar and some-times open dishes for tidbits.

A CRUET FRAME or CRUET STAND or BOTTLE STAND was often part of a dinner service, to hold condiment bottles or containers such as cruets, mustard pots, caster (shakers), and muffineers.

It became stylish in the early 18th century to have a silver stand that held oil and vinegar. A matching set of silver casters for several types of spices and sugar were also used. The two sets were joined together in one large silver frame as early as 1705.

Silver oil and vinegar bottle stands were usually in the form of small salvers with containers for the bottles and a tall handle to which the stoppers were attached by chains.

The design of the caster set changed about every 10 years. During the 18th and 19th centuries, many varied styles were made among which one of the most popular consisted of a boat—shaped stand with handles. In the early part of the 19th century, a circular type was introduced; and at the same time, individual bottles were supplied with bottle labels similar to those used on decanters to identify the casters.

BOTTLE LABELS were either painted or engraved with the name of the intended contents on the surface of the bottle or decanter. This decoration was not as common when the bottle tickets became popular.

BOTTLE TICKETS were small plaques suspended by a chain around the neck of a bottle or decanter. Bottle tickets may have already been lettered with the name of the contents or may have been left blank with the name of the contents to be added later.

TIPS FOR EXAMINING CRUETS AND SIMILAR ITEMS

NOTE: When examining cruets with handles, always pick up the cruet by the neck and not by the handle. If the handle is damaged, you might break it off.

Most cruets can safely be picked up in one hand by putting the thumb and several fingers around the neck and the forefinger over the top of the stopper so that the stop-per can’t fall out when the cruet is turned over for examination. It is safest to remove stoppers prior to examining cruets.

As far as cruets are susceptible to damage

(1) — Look for damage on the handle particularly where the handle is joined to the cruet at the spout and then where the handle is joined to the body of the cruet. (2) — Look for damage on the stopper or whether the stopper is original. (3) — Loss of an original cruet stopper will lower the value by as much as 25%. An original ground, polished stopper should turn snugly in the neck of the cruet without wobbling. (4) — Damage around the mouth and neck. (5) — Look around the body of the cruet and the base for chips or cracks. (6) — If it is wet inside at all, be aware of the fact that it might be "sick" glass. Let the rule of thumb be "Let the buyer beware" with any piece of glass that is wet inside or any dirt, sediment, stains, etc. You don’t know if the glass can be cleaned out or if it is "sick."

(7) — As there are numbers on the better pieces, the number on the stopper should generally match the number on the cruet. (8) — If you run across a very small oil or French bottle, it could be a perfume bottle that has had the applicator ground off because it was broken. (9) — Large mouth in cruet—like bottle is likely to be a ketchup (catsup) bottle. (10) —Cruet may have lip (or several) or NO lip — may have flat ring lip similar to cologne bottle. (11) — Vinegar cruet in multiple bottle set may be without stopper. Evaporation was not so much a problem with vinegar; as spoilage was with oil, therefore, the stopper.

BLOWING INTO PATTERNED MOULDS

The technique of blowing glass into moulds must have been developed the 1st century B.C., almost simultaneously with the discovery of how to blow glass. Once a gather of glass had been taken out of the furnace on the end of the blowing—iron, it was placed inside a mould. The mould, until the more modern period, would have been made of wood or clay, and would have had the required pattern formed on its interior surface. By blowing down the pipe, the worker could force the glass bubble into the shape of the mould. After being slightly cooled, the bubble was released from the mould and the blow—pipe was cracked off; when the vessel had been finished, it would be put to cool slowly in an annealing kiln. In modern times, moulds are kept wet, so that the steam caused by the hot bubble touching the mould forms a natural protection and ensures a longer life for the mould. Pattern moulds of wood would otherwise tend to burn away.

CUT & SHUT TECHNIQUE

- Pressed upside down, the plunger goes through the knockout piece inside the top.

- It is snapped up on the bottom, and the top is warmed in and finished.

(3) While held by a snap tool, the bottom is warm-ed in, closed and cut shut.