Late in 2007 the writer noticed a 7″D plate, cut in Hawkes’s patented Venetian pattern for sale at a local antiques group shop. Its sticker price was about 30% below what would normally be expected, suggesting that something was “wrong” about the item. It was housed in a wooden wall cabinet, where it was poorly illuminated. And there it stayed during the following several months.

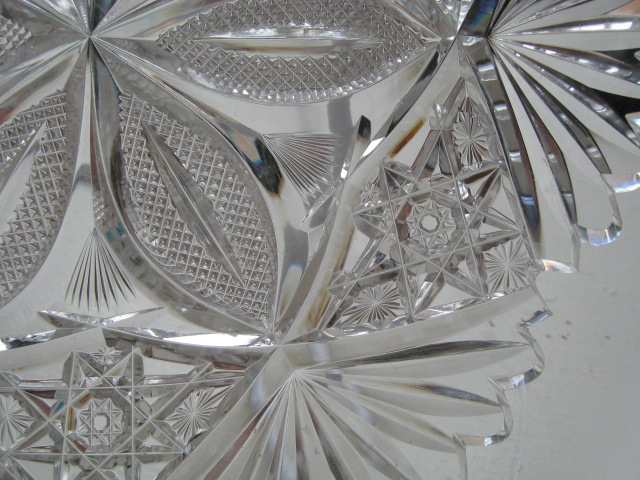

Later, in 2008, months after the plate was first exhibited, the writer asked the sales clerk to permit the plate to be examined. When it was taken from the cabinet it immediately “came alive” with a display of exceptional brilliance, an indication that the pattern was likely cut on a blank that had been obtained from C. Dorflinger & Sons. At the time the plate was made, during the 1890s, Dorflinger was producing top-quality blanks. Today these blanks compare favorably to the best of modern-day Steuben lead glass (as well as optical lead-glass blanks from various sources). During the years around 1900 blanks of this quality appear to have been in regular use by Hawkes for a series of patterns including Gladys, Devonshire, and others in addition to the Venetian pattern. Experience has shown that these patterns are “always” accurately cut on the top-quality blanks. With little hesitation, the writer bought the plate after examining it further as described in this file. But there are questions: Why did the writer’s Venetian plate remain unsold for such a long time? Was it because the pattern is simply not especially popular today? Perhaps.

THE PATENTED PATTERN

T. G. Hawkes & Company filed its application for a design patent with the U. S. Patent and Trademark Office for this pattern on 5 May 1890; the patent was granted on 3 Jun 1890. Subsequently, the pattern was named Venetian. This was not the first time Hawkes chose this name. In 1889 the company used the name Venetian for a patented pattern (which was actually the Brazilian pattern) not realizing that L. Straus & Sons had used this name earlier. To avoid confusion Hawkes changed the name of his 1889 pattern to Brazilian, and this is the name by which that pattern is known today. Today the name of Hawkes’s Venetian pattern is always restricted to the pattern that is under discussion in this file, patent no. 19,865.

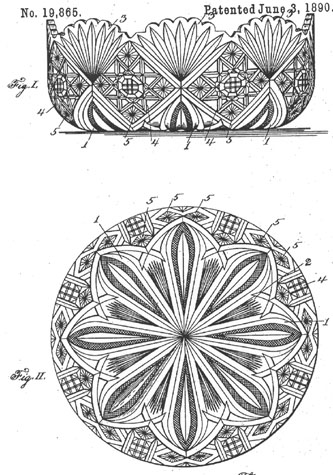

Although T. G. Hawkes, the designer must have had taken a course in engineering drawing while study an engineering curriculum in Ireland before he emigrated, and, therefore, he was probably adept at drafting his patent attorneys, Knight Brothers of Washington, DC probably assigned the patent’s drawing, as shown here, to their own draftsman as was customary at this time.

It is worthwhile noting the language used in the patent’s specification:

The leading features of my design consist in a large center star having elongated radiating ovate figures alternating with shorter fan-shaped figures, large fan figures extending outward

from the ovate figures, and star figures in the spaced between the ovate figures and the large fan figures, [the star figures] having rosettes at the corners of the spaces. [1] are the ovate figures, [2] the alternate fan figures, [3] the large fan figures, [4] the star figures, and [5] the rosettes in the corners of the spaces between the outer ends of the ovate

figures and the large fan figures.

Note that today the “ovate figures” would usually be called split vesicas, while the “large fan figures” are fan scallops, the “star figures” are 8-pt hobstars (also sometimes referred to as Middlesex-type hobstars), and the “rosettes” are single stars. Note that the name “rosettes” is ambiguous. It can also refer to other motifs by Hawkes and others; in fact, in his Chrysanthemum pattern Hawkes calls Brunswick stars “rosettes”. The term “rosettes” should be avoided in formal discussion.

Also note that the crossed figures on the 8-pt hobstars’ hobnails are not found on actual examples of the pattern. They are probably used here either because the designer had not made up his mind as to what motif to use or else because the hobstars that were actually chosen as the motif were too difficult to draw clearly. In practice, the hobstars’ hobnails are cut with 8-pt hobstars that have “uncut centers”. In other words, the motif that is often referred to as Middlesex-type hobstars.

THE VENETIAN PATTERN’S POPULARITY

The present file attempts to answer questions concerning the popularity of the Venetian pattern by first estimating what the pattern’s “popularity” was in 1978 and in 2005. Both of these estmates have their limitations, but they are the best that are currently available. Because they indicate that the Venetian pattern was not among those patterns that were especially highly rated at these dates, the writer accepts this as factual and concludes this file with some suggestions as to why this is so.

The first measure of “popularity” is the well-known rating scheme that was developed by J. Michael and (originally) Dorothy T. Pearson in 1969 and slightly revised by the senior author in 1978. The second measure was the American Cut Glass Association’s popularity poll conducted by the association’s Lone Star Chapter in 2005.

In the earlier of the first two books on American cut glass by J. Michael and Dorothy T. Pearson Hawkes’s Venetian pattern received high praise: “This pattern, patented June 3, 1890 by Thomas G. Hawkes is one of the most beautiful and rarest [patterns] of the Brilliant Period. . . . Any collector would be fortunate to acquire even a single piece.” (Pearson and Pearson 1965, p. 56 with patent drawings and two applications of the patent).

PEARSONS’ RELATIVE VALUE CHARTS OR GUIDE

When they published their second book in 1969, the Pearsons introduced a popularity-based system called “Price Guides, Frequency and Relative Value Charts” — to rationalize two characteristics of all well-known American cut-glass designs: their rarities (frequencies) and their quality/price ranges (relative values) as indicated by two numerals — for example, 2-1. The numbers in this system run from 1 to 10 with the lowest numbers assigned to patterns that were considered to be the rarest and/or of the highest quality. The patterns so evualuated were those that the Pearsons considered especially collectible. In the foregoing example, “2” indicates that a pattern is very rare, and “1” indicates that it is considered to be of highest quality. This is the rating the Pearsons originally gave to Hawkes’s Venetian pattern.

J. Michael Pearson slightly revised the ratings of this system in the third volume of his ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CUT AND ENGRAVED AMERICAN GLASS which was published in 1978, nine years after the scheme was first introduced. Here the Venetian pattern earned a “3” for rarity, which is still considered to be “very rare” and probably is not significantly different than the “2” assigned to it originally. It is, nevertheless, a bit odd that the pattern’s rarity would have decreased during the nine years that separate the two books, but this probably merely reflects the subjectivity involved and the difference should not be taken as significant. In fact, items rated both 2 and 3 are considered to be “very rare”. The Venetian pattern’s rating in the scheme’s quality/price range remained as originally indicated: “1” (highest category). At this time, as well as earlier, the Pearsons believed that their rarity and quality evaluations were “generally accepted by most collectors and dealers”.

Initially the Pearsons indicated that “These ratings are based on more than 15 years experience in handling tens of thousands of pieces [of cut glass] (emphasis added)”. In 1978 this statement — which must have raised an eyebrow or two (“tens of thousands of pieces”?) — was replaced with the following: “These ratings are based on actual examination of the glass itself in the patterns listed. Without an examination of the cut glass itself it is impossible to judge its quality and therefore [such] design[s] are not included in the Relative Value Chart” which is the current name of Pearson’s evaluation scheme.

In spite of the fact that Pearson’s Relative Value Charts or Guide (both terms are used) is used today on a regular basis by sellers of American cut glass, the scheme, in its final form of 1978 is now thirty years old. Undoubtedly both the availability (rarity) and the perceived quality/price range of individual patterns have changed over the years. Unfortunately, it is not possible to measure these changes today because we can not duplicate the procedure originally used by Pearson. The most we can do is obtain some other measure of a pattern’s “popularity” — one that can be considered to be objective at least to some degree.

The Lone Star Chapter of the American Cut Glass Association (ACGA) attempted such a “popularity contest” in 2005 when it sent a ballot to all of the members of the association. It contained 74 named patterns and permitted any number of write-ins. The result of this poll was reported in the February 2006 issue of The Hobstar, the association’s newsletter. The reader can consult this issue for details. For our purpose it is sufficient to note that while the poll can not be directly compared to the Pearsons’ quality ratings, it, nevertheless, does give an indication of the popularity, in 2005, of most of the patterns considered in Pearson’s rating scheme. Note, however, that only 255 ballots were returned by the more than one thousand members of the ACGA.

How does Hawkes’s Venetian pattern fare in the ACGA poll? Somewhat surprisingly, it garnered only 39 votes. The pattern that earned the most votes was the Alhambra pattern by Meriden with 117. If one converts each of the ACGA patterns to a percentage of the Alhambra pattern’s number, then the Venetian pattern has a rating of 33% — that is, the Venetian pattern can be said to be only one-third as popular as the ACGA’s most popular pattern, Alhambra. This is a disappointing result for those of us who continue to stand behind Pearson’s praise of 1965 (and repeated in 1978).

As an item of general interest the following lists contain the most popular and least popular of the ACGA patterns. “Write-ins” were not revealed in the poll’s results, except in the case of Libbey’s Marcella pattern which earned 20 votes and, therefore, if it were rated it would stand at 17% compared to the Alhambra pattern; in other words it would have earned a position immediately following the Rosemere pattern, below. This indicates the importance of having a pattern actually listed rather than being a write-in. One should also note that very rare patterns received relatively few votes, probably because one seldom sees them “alive”. This applies to a pattern such as Hawkes’s Coronet which is rated at only 14% while the even rarer pattern, “Maltese Cross”, does not appear at all (although it could have received a write-in vote or two). Remember: Alhambra’s 100% rating means that it received the most votes cast (117), not that it received a vote from each of the poll’s 255 participants.

The ten most-favorite cut-glass patterns:

1. 100% Alhambra (Meriden)

2. 92% Queens (Hawkes)

3. 84% “Rex” (Tuthill)

4. 81% Nautilus (Hawkes)

5. 78% Aztec (Libbey)

6. 75% Ellsmere (Libbey)

7. 74% Crystal City (Hoare)

8. 67% Chrysanthemum (Hawkes)

9. 66% Brunswick (Hawkes)

10. 66% Panel (Hawkes)

The ten least-favorite cut-glass patterns:

65. 20% Montrose (Dorflinger)

66. 20% Wheat (Hoare)

67. 19% “Cetus” (unknown)

68. 18% Rosemere (Tuthill)

69. 14% Coronet (Hawkes)

70. 14% Nordica (Blackmere)

71. 13% Berwick (Pairpoint)

72. 13% Kenwood (Bergen)

73. 12% Morello (Libbey)

74. 12% Plymouth (Pitkin & Brooks)

Because the book EVIDENCE OF CHANGE appeared after the ballots were distributed, no patterns designed by William C. Anderson EXCLUSIVELY for his own cutting shop are listed in the ACGA poll although, given the enthusiasm shown by the authors of this book, several such patterns would surely have received attention from the ACGA’s voters had the book been made available earlier.

Finally, to explain why Hawkes’s Venetian pattern is not more popular today than what it appears to be, the following suggestions are offered:

1. Drawings, U. S. Patent Office. The Venetian’s patent drawing has been readily available to collectors since 1950 (Daniel 1950, p. 232). Unfortunately the company submitted what appears to be a no. 700 bowl cut with the pattern to its patent attorneys who, in turn, had the pattern drawn by a professional draftsman, the usual procedure at this time. Because hollowware was submitted, and not flatware such as a plate, it was necessary for the draftsman to draw two illustrations in order to describe the patent completely — a profile view and a planimetric view, described in the patent’s specification as a side elevation and a bottom view of a glass bowl. As a result of this, it has not been possible for the collector, even the intermediate collector, to easily visualize the complete Venetian pattern. It is necessary to do this, however, in order to fully appreciate the pattern.

2. Application of the patented design to various shapes. This was often a problem for cutting shops, particularly when it was necessary to cut a pattern such as the Venetian on hollowware (vases, decanters, etc.). Because the design is not a border-type pattern, it was often necessary to limit the pattern in such a situation, usually by truncating it. The truncated pattern can be seen as somewhat unbalanced, and, therefore, not especially attractive. Occasionally, however, certain items of hollowware, such as carafes, sugars, and creamers, were cut in a “wrap-around” style that preserves the patent’s complete design as originally set forth in the letters patent.

In addition, even if it is not truncated, a pattern can become somewhat distorted when cut on shapes that deviate from the simple, round disk the designer usually had in mind (even though Hawkes used a bowl in his patent drawing for the Venetian pattern). Such distorations are readily found, for example, on items such as rectangular trays and on bon-bon dishes of various shapes. In such settings the Venetian pattern, like its truncated version, is not especially attractive.

3. Cut motifs that “overlap”. Usually, of course, overlapping motifs can indicate that the item has been clumsily repaired. This fault appears on the writer’s no. 350 7″D plate in the Venetian pattern that is referred to at the beginning of this file and pictured below. In this example the rim’s U-notches cut into the pattern’s outermost single stars. Additionally, the rim’s 9-ribbed fans are cut in such a manner that each rib does not necessarily correspond to the center of each of the rim’s smooth and pointed scallops — in fact, few do. However, if one compares this item to the example found in the c1897 Hawkes compilation catalog (incorrectly dated 1890) that was published by the ACGA in 2003 (p. 144), it is seen that both of these “faults” were present originally and are not the result of any re-cutting of the plate’s rim. Would-be buyers, nevertheless, may well take a “pass” on such an item, believing it to have been repaired. The writer feels that the seller of his 7″D plate is in this group. This would explain why the plate was priced well below “fair market value.”

Someday the writer might find this item without the so-called faults, but, even if he did, there would be no guarantee that such an example would present the Venetian pattern cutting on a blank of such superb quality. The plate is lovely just the way it is!

The writer considers that the Venetian pattern is truly one of the “great” patterns of the American brilliant period. Using the tripartite division of the American brilliant period, as suggested in the GUIDE, the Venetian pattern can be labeled a top-quality pattern from the middle brilliant sub-period (c1885-c1905), a time when American cut glass was at its best and excellent designs were plentiful. Today the pattern deserves a higher level of appreciation than what it actually receives!

Plate. Venetian pattern on blank (shape) no. 350 by Hawkes. This item is shown in the HAWKES PHOTOGRAPHIC FOLIO II of c1897, p. 144. (The folio is incorrectly dated c1890 by the publisher, ACGA, 2003.) Some light surface scratches. Two small areas of minor roughness on miters. D = 7.25″ (18.4 cm), H = 1.00″ (2.5 cm), wt = 1.1 lb (0.48 kg). Purchased for $200 in Corning, NY in 2008.

EPILOG

Colored wine glasses cut in the Venetian pattern, as displayed at the Corning Museum of Glass, 10 Mar 2009 (Image: JMH/CMoG). The set’s label reads as follows: “Six

Wineglasses, ‘Venetian’ Pattern. T. G. Hawkes and Company 1889-1900. 2006.4.163. These glasses are from a set of a dozen in a leather case. The set has two glasses in each color. The

rare color combinations were undoubtedly intended to display the skills of both blowers and cutters.” The full set was exhibited at CMoG’s “Splitting the Rainbow” exhibit, 11 Apr – 1 Nov

2006. See both the CMoG’s Annual Report 2006, pp. 32-33 and Spillman 2006 (The Gather, spring/summer, p. 5) for general accounts of the exhibit. Both references provide images in

color; the first one has an image of the leather case and its contents.

According to MIMSY the colors in the displayed set (above) are, clockwise from the upper left: green cut-to-clear (C*), amethyst cut-to-clear (F), cranberry cut-to-clear (J), apricot cut-to-clear (L), double red cut-to-clear (E), and red cut-to-yellow (I). This writer believes that the double red (E) and the red cut-to-yellow (I) glasses are open to alternative analyses.

* The letter indicates the suffix that is to be added to the accession number for the specific glass that is on display. Duplicate glasses are in storage for all of the glasses except the apricot cut-to-clear glass (L). Total number of glasses = 11.

The leather case and its contents were first registered in MIMSY on 5 Apr 2006 and then re-registered (updated) during Jan and Feb 2009, presumably at the time the glasses were lent to the annual NYC Winter Antiques Show.

Entries in MIMSY sometimes contain inaccuracies and are often incomplete. For example, a typical entry for a particular wine glass (C, above) reads as follows:

Green cut-to-colorless wineglass. Colorless and transparent dark green glass; blown, cased, tooled, applied, cut, polished. Hemispherical shaped green bowl cut in the “Venetian”

pattern sits atop a colorless stem with faceted knop and cirular foot with “rays” cut into the underside. COMMENT: Most collectors would consider that the bowl’s shape is more cup-shaped than hemispherical, and the description of the stem is incomplete: It is blown with an air trap

that runs its length and is cut with six flutes (panels). The faceted knop is located at the upper end of the stem, just below the bowl. Finally, the applied foot is cut with ridged

radiants, a distinctive motif that should have been identified.

Although the writer recalls that the leather case and its contents were displayed at the Splitting-the-Rainbow exhibit (2006) where they were described as being on loan, the Museum now owns the set. A search of MIMSY as well as the Museum’s publications did not confirm this, however, nor did the search reveal the circumstances surrounding the acquisition of the wine glasses, presumably at the conclusion of the exhibition (as a gift? purchase?). Such information will be of use to anyone who attempts to reconstruct the provenance of the wine glasses, itself a useful exercise but not one that the writer anticipates undertaking.